US Declare War On Iran: A Constitutional Conundrum

The question of whether the United States could, or should, declare war on Iran is not merely a hypothetical geopolitical exercise; it delves deep into the very fabric of American constitutional law, historical precedent, and the complex realities of modern international relations. For many, the idea of the US declare war on Iran conjures images of past conflicts, endless engagements, and profound societal costs. This concern is amplified by recent escalations in the Middle East, particularly the ongoing tensions between Israel and Iran, which inevitably draw the United States into a perilous dance on the brink of wider conflict.

Understanding the legal and political mechanisms that govern the use of military force by the United States is crucial, especially when discussing a potential declaration of war against a nation like Iran. The path to war, as envisioned by the U.S. Constitution, is deliberately arduous, reflecting the framers' intent to prevent hasty military entanglements. However, the realities of the post-World War II era, and particularly the post-9/11 landscape, have significantly blurred these lines, leading to a complex interplay between presidential power and congressional authority.

The Constitutional Mandate: Who Declares War?

At the heart of any discussion about the United States going to war lies Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. This foundational document unequivocally assigns the right to declare war to Congress. This deliberate allocation of power to the legislative branch was a cornerstone of the framers' vision, intended to ensure that the monumental decision to commit the nation to armed conflict would be made by the representatives closest to the people, after thorough debate and deliberation. It serves as a critical check on the executive branch, preventing a single individual from unilaterally plunging the nation into war.

This constitutional clarity, however, belies a far more complicated modern reality. While Congress retains the sole power to declare war, the nature of warfare has evolved dramatically since the 18th century. The advent of rapid global communication, the proliferation of non-state actors, and the need for swift responses to emerging threats have often led presidents to take military action without a formal declaration of war. This executive action, often framed as defensive measures or limited engagements, has progressively chipped away at the strict constitutional interpretation, leading to a persistent tension between the branches of government regarding war powers.

Historical Precedent: A Fading Congressional Power

The historical record vividly illustrates the erosion of Congress's explicit war-declaring power. The last time Congress formally declared war was at the beginning of World War II, when Franklin Roosevelt was president. Since then, the United States has engaged in numerous significant military conflicts—Korea, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf War, Afghanistan, Iraq, and various counter-terrorism operations—all without a formal congressional declaration of war. Instead, these actions have been authorized through resolutions, international agreements, or presidential executive orders, often citing national security interests or existing authorizations for the use of military force (AUMFs).

This trend highlights a significant shift in the balance of power, with the executive branch increasingly asserting its authority in foreign policy and military matters. While Congress still holds the "power of the purse" and can influence military operations through funding, its direct role in initiating large-scale conflicts has diminished. This historical pattern sets a challenging backdrop for any renewed calls for Congress to explicitly authorize military action, let alone a formal declaration of war, against a nation like Iran.

The War Powers Resolution: A Check on Executive Authority

In response to the perceived overreach of presidential power during the Vietnam War, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution (often referred to as the War Powers Act) in 1973. This landmark legislation aimed to reassert congressional authority over the use of military force. It requires the president to notify Congress within 48 hours of deploying armed forces into hostilities or situations where hostilities are imminent. Furthermore, it mandates that the president must withdraw troops within 60 days (with a possible 30-day extension) unless Congress has declared war, authorized the use of military force, or extended the period.

Despite its intent, the War Powers Resolution has been a source of ongoing dispute between the executive and legislative branches. Presidents have often viewed it as an unconstitutional infringement on their commander-in-chief powers, while Congress has frequently struggled to enforce its provisions. Its effectiveness in preventing unilateral presidential military action has been limited, leading many lawmakers to seek alternative ways to curb executive power, particularly in volatile situations that could lead to a full-scale conflict, such as a potential US declare war on Iran.

Congressional Efforts to Curb Presidential Power

In recent years, especially during periods of heightened tension with Iran, members of Congress from both sides of the aisle have actively sought to limit the president's ability to order U.S. strikes on Iran without explicit congressional approval. For instance, lawmakers have proposed measures that would bar the president from using the U.S. military against Iran without congressional approval or to terminate the use of U.S. armed forces against Iran without Congress.

A notable example includes Democratic lawmaker Tim Kaine, who introduced a bill aimed at curbing the president's power to go to war with Iran. Such measures underscore the deep-seated concern among lawmakers that the United States could be drawn into another "endless war" in the Middle East without proper constitutional oversight. They emphasize that "Congress has the sole power to declare war against Iran," and that even if the ongoing war between Israel and Iran were to escalate, "Congress must decide such matters according to our Constitution." These legislative efforts reflect a growing bipartisan desire to reclaim Congress's constitutional prerogative in matters of war and peace, particularly concerning a nation as strategically significant and volatile as Iran.

The Iran Context: Escalating Tensions and US Involvement

The specter of the United States engaging in direct conflict with Iran is a recurring theme in global geopolitics, fueled by decades of mistrust, sanctions, and proxy conflicts. Recent escalation of hostilities between Israel and Iran could quickly pull the United States into another endless conflict. This is a primary concern for many lawmakers and the public alike, who remember the costly engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The U.S. relationship with Iran is multifaceted, involving concerns over Iran's nuclear program, its support for various proxy groups in the region, and its human rights record. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, for example, has issued direct and forceful warnings to Iran following serious incidents, such as those involving Houthi drones, which further exacerbate tensions. While a development like this doesn't automatically mean that the U.S. has declared war on Iran or started joining Israel in its strikes on the country, it certainly indicates that things are at a stage where the U.S. is "pretty much ready to" respond forcefully to perceived threats. The very idea of the US declare war on Iran is often framed in the context of these escalating regional dynamics.

The Role of Proxies and Allegations of Support for Terrorism

A significant aspect of the U.S.-Iran dynamic involves Iran's alleged support for various regional groups, some of which are designated as terrorist organizations by the United States. For instance, Professor Kneeland noted that past presidents might use Iran's identification with supporting Hezbollah, listed as a terrorist organization in the U.S., as a pretext should they decide to attack Iran. This complex web of alliances and proxy warfare makes any potential conflict with Iran far more intricate than a traditional state-on-state confrontation. The blurred lines of engagement, particularly after laws passed after 9/11, further complicate the clarity on who could declare war or authorize military action against such entities, or against the state supporting them.

Public Opinion and Protests: Voices Against War

The prospect of military conflict with Iran is met with significant public opposition within the United States. Across U.S. cities, Iran war protests frequently break out, with people holding signs and demonstrating against potential military action. These protests reflect a deep-seated weariness with foreign military interventions and a strong desire to avoid another costly and protracted war in the Middle East. For many, the "ongoing war between Israel and Iran is not our war," and they believe that any decision to engage militarily should be made with the utmost caution and, crucially, with full congressional approval as mandated by the Constitution.

The public's voice, expressed through protests and advocacy, plays a vital role in shaping the political discourse around military intervention. Lawmakers are often responsive to public sentiment, especially on issues as consequential as war. The presence of widespread anti-war sentiment can act as a powerful deterrent against unilateral executive action and reinforce the calls for congressional oversight.

The Reality on the Ground: Are We Already There?

Despite the constitutional requirement for Congress to declare war, the reality of modern military engagements often blurs the lines between peace and conflict. The question isn't always whether the US declare war on Iran in a formal sense, but rather whether American military forces are already directly involved in a way that constitutes hostilities.

The presence of U.S. military assets in the region, the increasing frequency of incidents involving U.S. forces and Iranian-backed groups, and the rhetorical escalation from both sides create a volatile environment. While there might be no formal "declaration of war against Iran," and no evidence that U.S. troops are gathering in the United Arab Emirates in preparation to invade Iran, the stage is set for potential direct confrontation. The distinction between "military action," "hostilities," and "war" becomes increasingly semantic in such a high-stakes environment.

The Blurring Lines of Engagement

The legal landscape governing the use of military force has become increasingly complex. As Professor Kneeland noted, laws passed after 9/11, such as the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), blurred clarity on who could declare war. These broad authorizations, initially intended for counter-terrorism operations, have been interpreted by successive administrations to justify military actions far beyond their original scope, including against state actors perceived to be supporting terrorist groups. This legal ambiguity allows for military engagement without the explicit, targeted congressional authorization that a formal declaration of war would entail.

The question then becomes: at what point do these "limited" engagements or "defensive" actions cross the threshold into an undeclared war? This is precisely the dilemma that Congress faces, as it tries to reassert its constitutional role in an era where conflicts are often characterized by drone strikes, cyber warfare, and proxy battles rather than traditional invasions.

The Absence of a Formal Declaration

It is crucial to reiterate that despite the heightened tensions and military posturing, there has been no formal "declaration of war against Iran" by the United States Congress. Furthermore, there is no public evidence to support claims of a massive deployment, such as the Pentagon dispatching "150,000 troops trained in street fighting to the United Arab Emirates in preparation to invade Iran." Such rumors often circulate during periods of geopolitical uncertainty but lack official confirmation.

The absence of a formal declaration, however, does not mean the absence of risk. The very act of introducing a joint resolution to authorize the use of United States armed forces against the Islamic Republic of Iran for threatening national security through nuclear weapons development indicates the seriousness with which some lawmakers view the situation. While such a resolution is not a declaration of war, it is a significant step towards formalizing military action, and its consideration alone underscores the precarious balance in the region.

The Path Forward: Avoiding a Full-Scale Conflict

Avoiding a full-scale conflict with Iran remains a paramount objective for many, both within the U.S. government and among the general public. The economic, human, and geopolitical costs of such a war would be immense, potentially destabilizing the entire Middle East and having far-reaching global consequences.

The path forward requires a delicate balance of diplomacy, deterrence, and a clear understanding of constitutional prerogatives. It necessitates that the executive branch consults with and gains the explicit approval of Congress before committing U.S. forces to hostilities against Iran. It also demands that Congress actively exercises its constitutional duty to debate and decide on matters of war and peace, rather than deferring to executive action. The ongoing efforts by lawmakers to introduce legislation that limits presidential war powers are a testament to this renewed emphasis on constitutional checks and balances. Ultimately, preventing the US declare war on Iran without proper deliberation and authorization is not just a legal requirement but a moral imperative.

Table of Contents

- The Constitutional Mandate: Who Declares War?

- Historical Precedent: A Fading Congressional Power

- The War Powers Resolution: A Check on Executive Authority

- The Iran Context: Escalating Tensions and US Involvement

- Public Opinion and Protests: Voices Against War

- The Reality on the Ground: Are We Already There?

- The Path Forward: Avoiding a Full-Scale Conflict

The question of whether the United States will formally declare war on Iran remains highly contentious and unlikely, given modern political realities. However, the risk of escalating hostilities and the United States being drawn into an undeclared conflict is ever-present. The constitutional framework, designed to prevent unilateral executive action, is under constant pressure in an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape. It is imperative that both the public and their representatives remain vigilant, upholding the principles of democratic oversight in matters of war and peace.

What are your thoughts on the balance of power between the President and Congress when it comes to military action? Share your perspectives in the comments below, or consider exploring other articles on our site that delve into U.S. foreign policy and constitutional law.

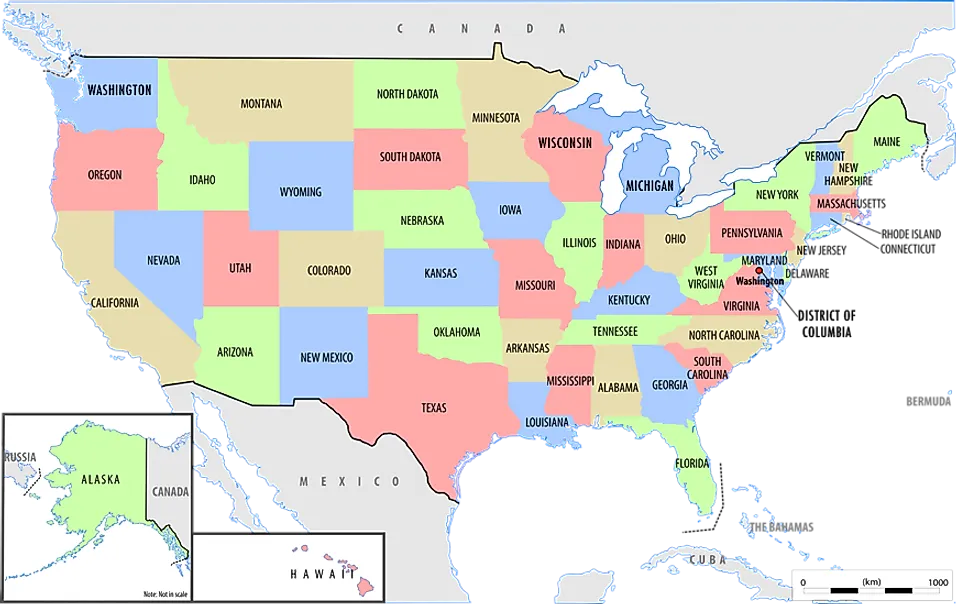

USA Map. Political map of the United States of America. US Map with

United States Map Maps | Images and Photos finder

Mapas de Estados Unidos - Atlas del Mundo