Iran Before The Revolution: A Look Back At A Transformed Nation

Before the Islamic Revolution swept through Iran in 1979, fundamentally reshaping every facet of its society, the nation existed as a remarkably different world. This pivotal period, often referred to as pre-Islamic Revolution Iran, represents a fascinating chapter in modern history, marked by ambitious modernization, significant social shifts, and underlying tensions that would eventually erupt into a transformative upheaval. Understanding this era is crucial to grasping the complexities of contemporary Iran and the enduring legacy of its imperial past.

The stark contrast between Iran before and after 1979 is undeniable. From a society that was rapidly embracing Western norms, pushing for secular reforms, and seeing women achieve unprecedented levels of public participation, Iran transitioned into an Islamic Republic. This article delves into the vibrant, yet volatile, landscape of pre-Islamic Revolution Iran, exploring the aspirations, achievements, and inherent contradictions that paved the way for one of the 20th century's most significant political and social transformations.

Table of Contents

- The Pahlavi Dynasty: Architects of Modernization

- A Vision of Progress: Social Reforms and Secularism

- Women's Rights: A Shifting Landscape

- Economic Transformation and Geopolitical Significance

- Seeds of Discontent: The Shah's Unsteady Grip

- The Clergy's Resurgence and Traditional Opposition

- Social Upheaval and Growing Dissatisfaction

- The Road to Revolution: Escalating Protests

- A Nation Transformed: The Aftermath of 1979

- Legacy and Lessons from Pre-Revolutionary Iran

The Pahlavi Dynasty: Architects of Modernization

The narrative of pre-Islamic Revolution Iran is inextricably linked to the Pahlavi dynasty, particularly the reigns of Reza Shah Pahlavi and his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. From 1941 to 1979, Iran was ruled by King Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, known simply as the Shah. Both father and son harbored ambitious visions of transforming Iran into a modern, developed nation, drawing inspiration from figures like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who had dramatically modernized Turkey. Their approach was top-down, often autocratic, and aimed at rapid societal change, frequently at the expense of traditional structures and fundamental rights.

The Pahlavi era was characterized by a concerted effort to introduce Western-style modernity. This included reforms in education, legal systems, and infrastructure. The Shahs believed that by shedding traditional customs and embracing secularism, Iran could join the ranks of developed nations. However, this push for modernization often alienated significant portions of the population, particularly those deeply rooted in religious and traditional values. The suppression of dissent and the centralization of power under the Shah further fueled underlying discontent, creating a volatile environment even amidst apparent progress.

A Vision of Progress: Social Reforms and Secularism

Under the Pahlavi regime, Iran witnessed a deliberate and often forceful drive towards secularism. Reza Shah, in particular, sought to diminish the influence of the clergy and integrate religious institutions into the state apparatus. This included reforms in the judicial system, moving away from Sharia law towards a more secular legal framework. The government also invested heavily in public education, establishing universities and promoting literacy, aiming to foster a more educated and secular populace.

The traditional and extended families, which had long held prominence in Iranian society, began to see their influence wane with the rise of secularism. The Shah’s autocratic policies, while aiming for progress, often suppressed fundamental rights, leading to a complex societal dynamic where outward modernization coexisted with deep-seated grievances. This period laid the groundwork for significant social transformation, but also sowed the seeds of future conflict as different segments of society grappled with the pace and direction of change.

- Isanyoneup

- Meganmccarthy Onlyfans

- Aitana Bonmati Fidanzata

- Judge Ross Wife

- How Old Is Jonathan Roumie Wife

Women's Rights: A Shifting Landscape

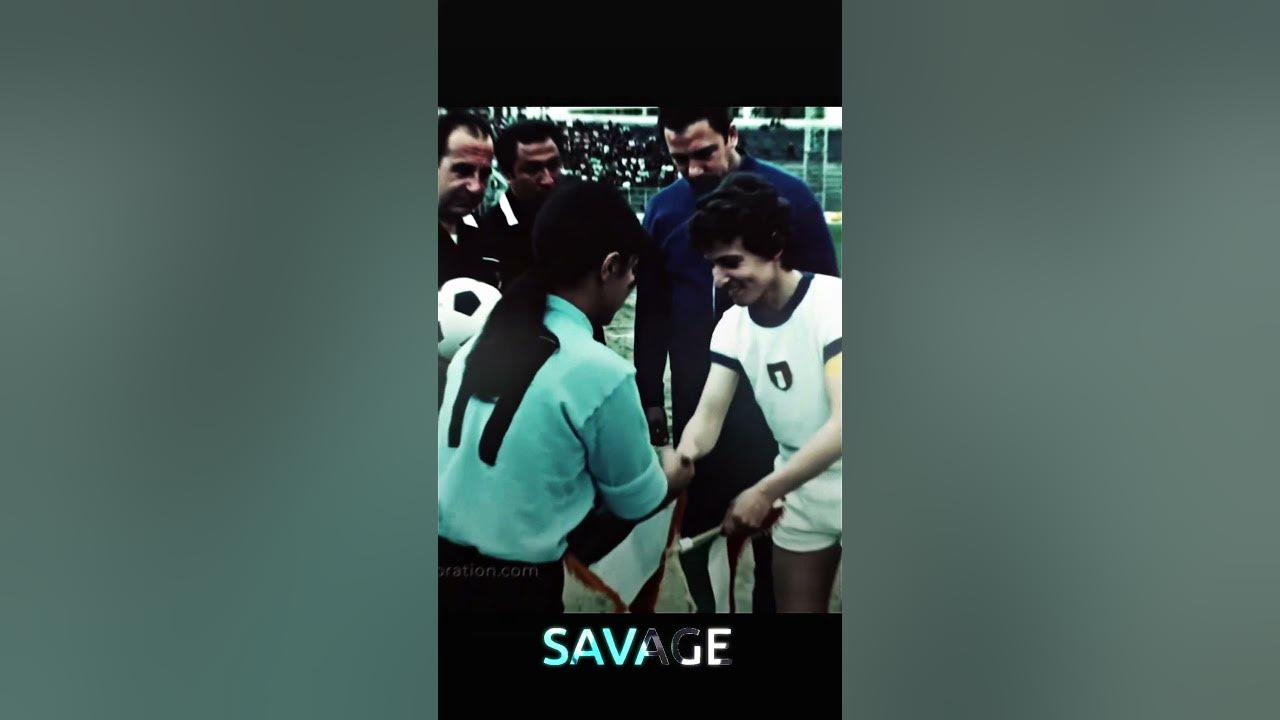

Perhaps one of the most striking transformations in pre-Islamic Revolution Iran occurred in the realm of women's rights and social standing. It was a world that was looking brighter for women, with significant advancements in education, employment, and public life. Before 1979, Iranian women wore miniskirts, earned advanced degrees, ran businesses, and lived lives that looked remarkably like their Western peers. This was a direct result of the Pahlavi regime's modernization agenda, which actively sought to bring women into the public sphere and empower them through education and employment.

The statistics from the eve of the Islamic Revolution paint a vivid picture of this progress:

- Nearly 2 million women were gainfully employed in public and private sectors.

- 187,928 women were studying in various branches of Iran’s universities, indicating a massive leap in educational opportunities.

- Of nearly 150,000 women employees of the government, 1,666 occupied managerial positions, demonstrating their growing presence in leadership roles.

- Women also held political office, with 22 Majlis deputies and two senators, one ambassador, and three deputy ministers, showcasing their increasing political participation.

Economic Transformation and Geopolitical Significance

Pre-Islamic Revolution Iran was a nation undergoing significant economic transformation, largely driven by its vast oil reserves. This immense supply of oil not only fueled Iran's domestic modernization efforts but also cemented its crucial geopolitical position. Due to Iran's vast supply of oil, proximity to India, and shared border with the Soviet Union, Britain and the US fully backed the Iranian government. This strategic importance meant that Western powers had a vested interest in the stability and alignment of the Shah's regime, often overlooking its autocratic tendencies.

The oil wealth allowed the Shah to invest heavily in infrastructure, industry, and military capabilities, aiming to make Iran a regional powerhouse. Cities like Tehran experienced rapid growth, with modern buildings and amenities reflecting the nation's newfound prosperity. Iconic landmarks, such as Sepah Square, the main square in Tehran, captured the essence of a city striving for modernity, even as early as April 20, 1946. However, this economic growth was not evenly distributed. A significant portion of the population, particularly in rural areas, felt left behind, leading to a widening gap between the rich and the poor, and between the urban elite and the traditional masses. This disparity, coupled with perceptions of corruption and Western influence, would become a potent source of popular discontent.

Seeds of Discontent: The Shah's Unsteady Grip

Despite the outward appearance of stability and progress, the Shah's grip on power in pre-Islamic Revolution Iran was unsteady, even decades before the revolution. The foundations of this instability were laid much earlier, notably in 1953, over two decades before the Islamic Revolution. In that year, the CIA and British spy agency MI6 orchestrated the overthrow of Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh. Mossadegh had sought to nationalize Iran's oil industry, a move that threatened British and American interests. This foreign intervention, though successful in restoring the Shah to full power, left a deep scar on the collective Iranian psyche, fostering a profound distrust of Western influence and the Shah's legitimacy.

This event, meticulously detailed in works like "All the Shah's Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror" by Stephen Kinzer and "The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran" by Andrew Scott Cooper, demonstrated that the Shah's rule was not entirely indigenous but supported, and at times manipulated, by external powers. This perception of foreign puppetry, combined with the Shah's autocratic rule and the suppression of political freedoms, created a fertile ground for opposition movements to germinate, even if they remained largely underground for a period.

The Clergy's Resurgence and Traditional Opposition

A significant force opposing the Shah's modernization drive was the Shi'a clergy. Their powers, which had been extensive historically, were cut short by the Shahs' secular reforms. The clergy, feeling marginalized and threatened by the Westernization of Iranian society, wanted to gain back control and restore traditional Islamic values. They viewed the Shah's reforms, particularly those concerning women's rights and secular education, as an affront to Islamic principles and a betrayal of Iran's cultural identity.

Under the leadership of figures like Ruhollah Khomeini, who was exiled but maintained a powerful influence through his teachings and clandestine networks, the clergy became a focal point for discontent. They skillfully articulated the grievances of the disenfranchised, the religiously conservative, and those who felt alienated by the rapid pace of change. Their critique was not just religious; it encompassed social injustice, economic inequality, and the perceived subservience of the Shah to Western interests. This growing religious opposition, rooted in centuries of tradition and moral authority, posed a formidable challenge to the secular aspirations of pre-Islamic Revolution Iran.

Social Upheaval and Growing Dissatisfaction

The period leading up to Iran's Islamic Revolution was a time of major upheaval and reform, but also of escalating social dissatisfaction. While the Shah's regime pushed for modernization, it simultaneously fostered a widening chasm between different segments of society. The rapid pace of Westernization clashed with deeply ingrained cultural and religious traditions, creating a sense of disorientation and loss for many Iranians. The benefits of the oil boom were not equitably distributed, leading to stark economic disparities. The burgeoning middle class, educated and exposed to Western ideals of democracy, grew increasingly frustrated with the lack of political freedoms and the Shah's autocratic policies that suppressed fundamental rights.

Furthermore, the Shah's secret police, SAVAK, brutally suppressed dissent, leading to widespread fear and resentment. This suppression, rather than extinguishing opposition, merely pushed it underground, allowing it to fester and grow in intensity. The disconnect between the government's narrative of progress and the lived realities of many Iranians fueled a pervasive sense of injustice and a yearning for change. This complex interplay of social, economic, and political grievances created a highly combustible environment, ready to ignite at the slightest spark.

The Road to Revolution: Escalating Protests

As the 1970s progressed, the simmering discontent in pre-Islamic Revolution Iran began to boil over into widespread protests. Initially sporadic, these demonstrations grew in size and frequency, fueled by a coalition of students, intellectuals, the working class, and crucially, the religious establishment led by Ayatollah Khomeini. The Shah's attempts at reform were too little, too late, and often perceived as insincere. The use of force to quell protests only served to radicalize the opposition and galvanize public opinion against the regime.

The events of this period laid the foundation for the establishment of the Islamic Republic, ushering in a new era in Iranian history. Each protest, each crackdown, chipped away at the Shah's authority, demonstrating the growing power of the revolutionary movement. The sheer scale of public participation, particularly during religious holidays and political anniversaries, signaled the irreversible decline of the imperial system. The Pahlavis and the final days of imperial Iran were marked by a tragic miscalculation of the depth of popular anger and the enduring appeal of the religious opposition.

A Nation Transformed: The Aftermath of 1979

On February 11, 1979, the Islamic Revolution swept the country, marking the definitive end of pre-Islamic Revolution Iran. The Shah fled, and Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile to establish the Islamic Republic. This event dramatically transformed every aspect of Iranian society, from its political structure and legal system to its social norms and cultural identity. The changes were immediate and profound. Women, who had enjoyed significant freedoms and public roles, saw their rights curtailed, with mandatory veiling and segregation becoming the norm. The secular institutions that the Pahlavis had painstakingly built were dismantled or brought under religious control.

Before and after the revolution, Iran has undergone two major revolutionary changes in the twentieth century, but none as impactful and far-reaching as the 1979 revolution. The transition from a monarchy with aspirations of Western modernity to a theocratic state represented a fundamental reorientation of Iran's national identity and its place in the world. This dramatic shift continues to shape Iran's domestic policies and international relations to this day, making the study of its pre-revolutionary past essential for understanding its present.

Legacy and Lessons from Pre-Revolutionary Iran

The legacy of pre-Islamic Revolution Iran is complex and multifaceted. It was an era of paradoxes: rapid modernization alongside deep-seated traditionalism, economic growth coupled with social inequality, and a push for secularism met with a powerful religious resurgence. The events of this period laid the foundation for the establishment of the Islamic Republic, demonstrating how even seemingly stable regimes can crumble under the weight of popular discontent, especially when combined with a powerful, organized opposition and perceived foreign interference.

Understanding pre-Islamic Revolution Iran offers crucial insights into the dynamics of social change, the impact of modernization on traditional societies, and the enduring power of religious and cultural identity. It serves as a reminder that societal transformations are rarely linear and often involve profound clashes between competing visions for a nation's future. The story of Iran before 1979 is not just a historical account; it is a vital lesson in the intricate interplay of politics, culture, and power that continues to resonate globally.

We hope this deep dive into pre-Islamic Revolution Iran has provided you with a clearer understanding of this pivotal period. What are your thoughts on the transformations Iran underwent? Share your insights and questions in the comments below, or explore our other articles on historical turning points and their lasting impacts.

- Sophie Rain Spiderman Video Online

- Sandra Smith Political Party

- Maligoshik Leak

- Daisy From Dukes Of Hazzard Now

- Judge Ross Wife

Iran (Persia Before the Islamic Revolution) to Now | @drue86 | Sunny's

Iran before the Islamic Revolution of 1979 - YouTube

Was Iran better Before Islamic Revolution? #geography #history #india #