The Shah Of Iran: A Monarch's Ambition And A Nation's Destiny

The story of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, often simply referred to as the Shah of Iran, is one of immense power, grand ambition, and ultimately, a dramatic downfall that reshaped an entire region. His reign, spanning from 1941 to 1979, represents a pivotal era in Iran's modern history, marked by rapid modernization, imperial aspirations, and a growing chasm between the monarch and his people. Understanding the complexities of his rule is crucial to grasping the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East and the enduring legacy of the Pahlavi dynasty.

From his early life to his final days in exile, the Shah's journey was intertwined with Iran's destiny. He envisioned a powerful, modern Iran, a beacon of progress in the Islamic world, yet his methods and the consequences of his policies led to a revolution that forever altered the course of the nation. This article delves into the life, reign, and ultimate demise of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, exploring the forces that shaped his rule and the indelible mark he left on history.

Table of Contents

- Biography: Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi

- The Rise of a Monarch: Early Life and Education

- The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Imperial Ambition

- The Empress and Women's Rights: A Symbol of Progress

- The Shadow of SAVAK: Repression and Dissent

- The Seeds of Revolution: Growing Unrest

- Exile and Legacy: The Final Chapter

Biography: Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi

Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavi, born on October 26, 1919, was the last Shah (King) of Iran, reigning from September 16, 1941, until his overthrow by the Iranian Revolution on February 11, 1979. He ascended to the throne during a tumultuous period, inheriting a nation caught between the ambitions of great powers and the yearning for self-determination. His reign was characterized by ambitious modernization programs, a strong pro-Western foreign policy, and an increasing reliance on a powerful, centralized state apparatus. While he brought significant economic and social changes to Iran, his authoritarian rule and perceived disregard for traditional values ultimately fueled the revolutionary fervor that led to his downfall. The figure of the Shah of Iran remains a complex and often debated subject in historical discourse.

- Hubflix Hindi

- Marietemara Leaked Vids

- Tyreek Hill Hight

- Prince William Reportedly Holds A Grudge Against Prince Andrew

- Brennan Elliott Wife Cancer

Personal Data: Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavi |

| Title | Shah of Iran (Shahanshah – King of Kings) |

| Reign | September 16, 1941 – February 11, 1979 |

| Born | October 26, 1919, Tehran, Iran |

| Died | July 27, 1980, Cairo, Egypt |

| Father | Reza Shah Pahlavi |

| Mother | Taj ol-Molouk |

| Spouses | Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (m. 1939; div. 1948) Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary (m. 1951; div. 1958) Farah Diba (m. 1959) |

| Children | Shahnaz Pahlavi, Reza Pahlavi, Farahnaz Pahlavi, Ali Reza Pahlavi, Leila Pahlavi |

| Dynasty | Pahlavi Dynasty |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

The Rise of a Monarch: Early Life and Education

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi's early life, family, and education were instrumental in shaping the future monarch. Born into a newly established dynasty, his father, Reza Shah, had seized power in 1925, ending the Qajar dynasty and initiating a period of rapid, top-down modernization. This upbringing instilled in the young Mohammad Reza a profound sense of destiny and the weight of his family's mission to transform Iran. He was educated in Switzerland, attending Le Rosey, a prestigious boarding school, where he gained exposure to Western thought, culture, and political systems. This international education profoundly influenced his worldview, fostering a belief in the necessity of modernizing Iran along Western lines.

Upon his return to Iran, he enrolled in the Military Academy in Tehran, further solidifying his understanding of power and governance. His ascension to the throne in 1941 was unexpected and hastened by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran during World War II, which forced his father's abdication. At just 21, the young Shah of Iran inherited a country under foreign occupation, a challenging start that would define his early years in power and fuel his determination to assert Iran's sovereignty and global standing.

The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Imperial Ambition

The Shah of Iran harbored a grand vision for his country: to transform it into a modern, industrialized, and powerful nation, a regional superpower that would command respect on the world stage. He saw himself as heir to the kings of ancient Iran, drawing a direct line from the Achaemenid and Sasanian empires to his own reign. This deep-seated historical consciousness manifested in grand gestures designed to elevate Iran's image and reinforce the monarchy's legitimacy.

In 1971, he held an extravagant celebration of 2,500 years of Persian monarchy at the ancient ruins of Persepolis. This opulent event, attended by world leaders and royalty, was a monumental display of Iran's historical depth and the Shah's ambition, costing an estimated $100 million (a significant sum at the time). While it showcased Iran's wealth and heritage to the world, it also drew criticism domestically for its lavishness amidst widespread poverty.

Further demonstrating his break from traditional Islamic institutions and his embrace of a pre-Islamic, imperial identity, in 1976 he replaced the Islamic calendar with an imperial calendar, which began with the foundation of the Persian Empire more than 25 centuries earlier. This move, while intended to bolster national pride and the monarchy's historical roots, was deeply unpopular with religious conservatives and many ordinary citizens, who viewed it as an affront to their Islamic identity.

The White Revolution: Reshaping Iran

Central to the Shah's modernization efforts was the "White Revolution," a series of far-reaching reforms launched in 1963. These reforms aimed to address deep-seated social and economic issues, prevent a "red" (communist) revolution, and consolidate the Shah's power. Key components included land reform, which aimed to redistribute land from large landowners to peasants; nationalization of forests and pastures; the sale of state-owned factories to finance land reform; and the establishment of literacy and health corps to bring education and healthcare to rural areas. The White Revolution also included provisions for women's suffrage and the creation of profit-sharing schemes for industrial workers.

While these reforms brought some tangible benefits, particularly in education and infrastructure, their implementation was often top-down and disruptive. Land reform, for instance, sometimes led to fragmented landholdings and rural displacement, while the rapid urbanization it spurred strained city resources. The reforms also alienated powerful traditional groups, including large landowners and the religious establishment (ulama), who saw their influence diminished. This growing discontent would later become a significant factor in the eventual opposition to the Shah of Iran.

Asserting Power: Iran as a Regional Force

Under the Shah's rule, Iran emerged as the dominant power in Southwest Asia in the early 1970s. Bolstered by soaring oil revenues following the 1973 oil crisis, the Shah invested heavily in modernizing Iran's military, acquiring advanced weaponry from the United States and other Western nations. He positioned Iran as a key strategic ally of the West, particularly the United States, in containing Soviet influence and maintaining stability in the Persian Gulf region.

This assertive foreign policy saw Iran play an active role in regional affairs, from supporting pro-Western regimes to intervening in conflicts such as the Dhofar Rebellion in Oman. The Shah envisioned Iran as the "policeman of the Persian Gulf," a role that enhanced his international standing but also led to accusations of regional hegemony and increased military spending that diverted resources from other pressing domestic needs. The image of the Shah of Iran as a powerful, indispensable ally was central to his global persona.

The Empress and Women's Rights: A Symbol of Progress

One of the most visible aspects of the Shah's modernizing agenda was his commitment to advancing women's rights. His decision in 1967 to crown Farah Diba as Empress of Iran (Shahbanu) and appoint her regent in the event of his premature death symbolized his staunch commitment to full equality for women. This was a revolutionary move in a traditionally conservative society, elevating the status of the monarch's wife to an unprecedented level of political significance.

Empress Farah became a prominent public figure, actively involved in social and cultural initiatives, including education, healthcare, and the arts. Under the Shah's reign, women gained the right to vote, run for office, and pursue higher education and professional careers. Family laws were reformed to grant women more rights in marriage and divorce, though these reforms were still limited compared to Western standards. While these advancements were celebrated by many, particularly educated urban women, they were also viewed with suspicion and hostility by religious conservatives who perceived them as an erosion of Islamic values and a Western imposition.

The Shadow of SAVAK: Repression and Dissent

Despite the Shah's modernization efforts and the veneer of progress, his rule was increasingly characterized by authoritarianism and repression. The SAVAK, Iran’s notorious secret police, became synonymous with torture and surveillance, instilling fear among dissidents and activists. Established with the help of the CIA and Mossad, SAVAK grew into a pervasive force, monitoring and suppressing any form of opposition to the Shah's regime.

Political freedoms were severely curtailed. Political parties were largely co-opted or banned, and freedom of expression was heavily restricted. Thousands of political prisoners were held, and reports of torture and extrajudicial killings were rampant. This systematic repression, while effective in maintaining the Shah's grip on power in the short term, ultimately fueled deep resentment and pushed opposition movements underground, where they coalesced around religious figures and radical ideologies. The pervasive fear instilled by SAVAK meant that public discontent often simmered beneath the surface, only to erupt with devastating force when the opportunity arose. The legacy of SAVAK remains a dark chapter in the history of the Shah of Iran's rule.

The Seeds of Revolution: Growing Unrest

By the mid-1970s, despite Iran's economic growth fueled by oil wealth, the Shah's regime faced a confluence of challenges that would ultimately lead to its undoing. Rapid modernization had created social dislocations, widening the gap between the rich and poor and fueling a sense of alienation among those left behind. The economic boom also brought inflation and corruption, which further eroded public trust.

The Shah's secularizing policies, including the adoption of the imperial calendar and the promotion of Western culture, deeply offended the powerful religious establishment and a significant portion of the devout population. The repression enforced by SAVAK meant that legitimate political grievances had no outlet, forcing opposition into mosques and religious networks, where the charismatic leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled in Iraq and later France, gained immense traction. Khomeini's message, critical of the Shah's perceived subservience to the West and his disregard for Islamic principles, resonated deeply with a population tired of authoritarianism and yearning for cultural authenticity. The Shah of Iran, seemingly powerful on the surface, was increasingly isolated from the true sentiments of his people.

Exile and Legacy: The Final Chapter

The Iranian Revolution gained unstoppable momentum in late 1978, with widespread protests, strikes, and clashes. Facing overwhelming opposition and losing the support of key military figures, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi left Iran on January 16, 1979, ostensibly for a "vacation." This departure marked the effective end of the Pahlavi dynasty and the beginning of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The Shah spent his final year and a half in a painful and peripatetic exile, seeking medical treatment for his cancer while being shunned by many former allies who feared angering the new Iranian revolutionary government. He traveled from Egypt to Morocco, the Bahamas, Mexico, and finally the United States, where his entry for medical treatment sparked the Iran hostage crisis. Eventually, Mohammad Reza Shah died in exile in Egypt on July 27, 1980, where he had been granted political asylum by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. His death marked the definitive end of the Pahlavi monarchy.

The Pahlavi Dynasty in Exile

Following his father's death, his son Reza Pahlavi declared himself the new Shah of Iran in exile. He continues to advocate for a secular, democratic Iran, often expressing support for human rights and political freedoms. While he commands respect among a segment of the Iranian diaspora and some inside Iran who long for a return to a more secular state, the practical prospects of a monarchical restoration remain highly uncertain. The Pahlavi dynasty in exile represents a symbolic continuity of a past era, but its influence on contemporary Iranian politics is limited.

A Contested Legacy

The legacy of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi is highly contested, both within Iran and among international observers. Supporters point to his efforts to modernize Iran, build infrastructure, expand education, and empower women, transforming a largely agrarian society into a regional economic and military power. They argue that his vision, if allowed to continue, would have led Iran to greater prosperity and stability.

Critics, however, emphasize his authoritarianism, the brutal repression by SAVAK, his disregard for democratic principles, and the widening social inequalities that fueled popular resentment. They argue that his top-down modernization alienated traditional society and that his close ties to the West undermined Iran's independence. Ultimately, the Shah of Iran's reign stands as a complex historical narrative, a testament to the challenges of rapid change, the perils of unchecked power, and the enduring struggle between tradition and modernity in a nation with a rich and ancient heritage.

Conclusion

Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi's reign was a period of profound transformation for Iran, characterized by ambitious modernization drives and a determined effort to elevate the nation's standing on the global stage. From the grand celebrations of ancient Persian monarchy to the significant strides in women's rights and the assertion of Iran's regional power, the Shah's vision was undeniable. Yet, this vision was shadowed by an increasingly authoritarian rule, epitomized by the feared SAVAK, and a growing disconnect with the very people he sought to lead into modernity. His ultimate downfall and death in exile serve as a powerful reminder that even the most ambitious of monarchs can be undone by the forces of popular discontent and a failure to adapt to the changing tides of history.

The story of the Shah of Iran is not merely a historical account; it offers crucial insights into the complexities of nation-building, the delicate balance between progress and tradition, and the enduring consequences of political repression. What are your thoughts on the Shah's legacy? Do you believe his modernization efforts were ultimately beneficial despite their controversial aspects? Share your perspective in the comments below, and consider exploring other articles on our site that delve deeper into the history and politics of the Middle East.

- Paris Jackson Mother Debbie Rowe

- Jameliz Onlyfans

- Aishah Sofey Leaks

- Maria Temara Leaked Videos

- Morgepie Leaked

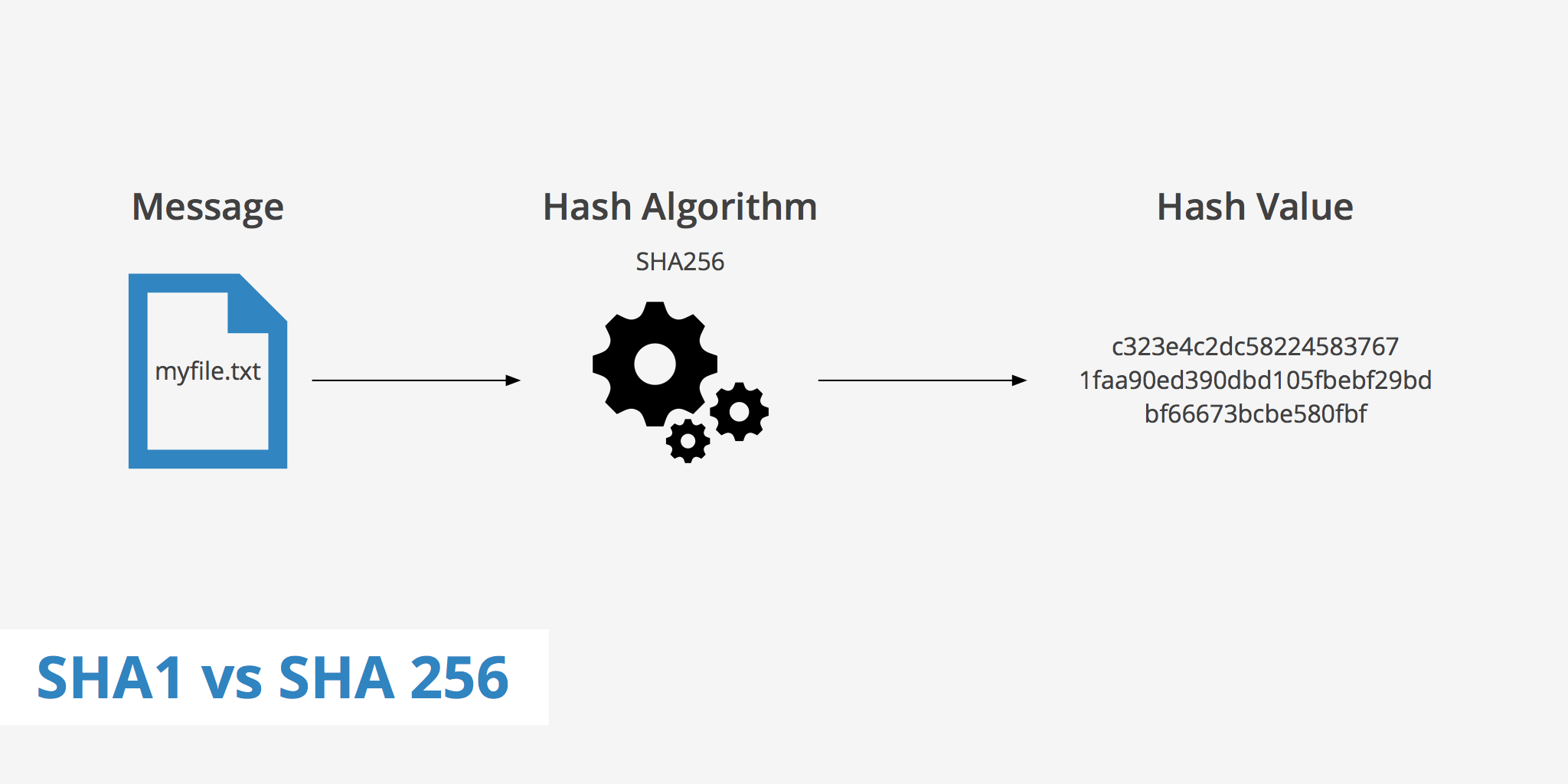

SHA1 vs SHA256 - KeyCDN Support

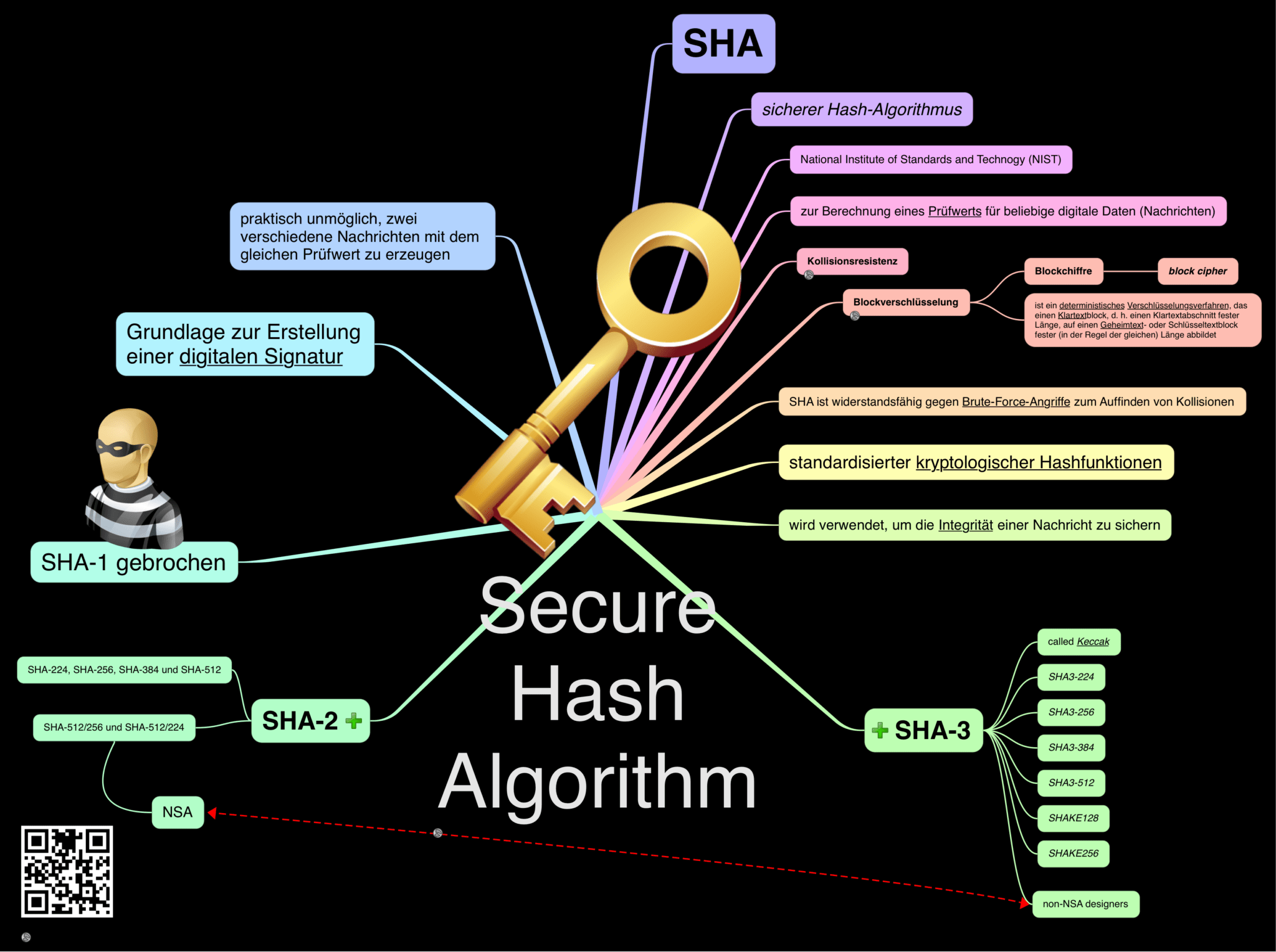

Secure Hash Algorithm – SHA – Das Kleinhirn

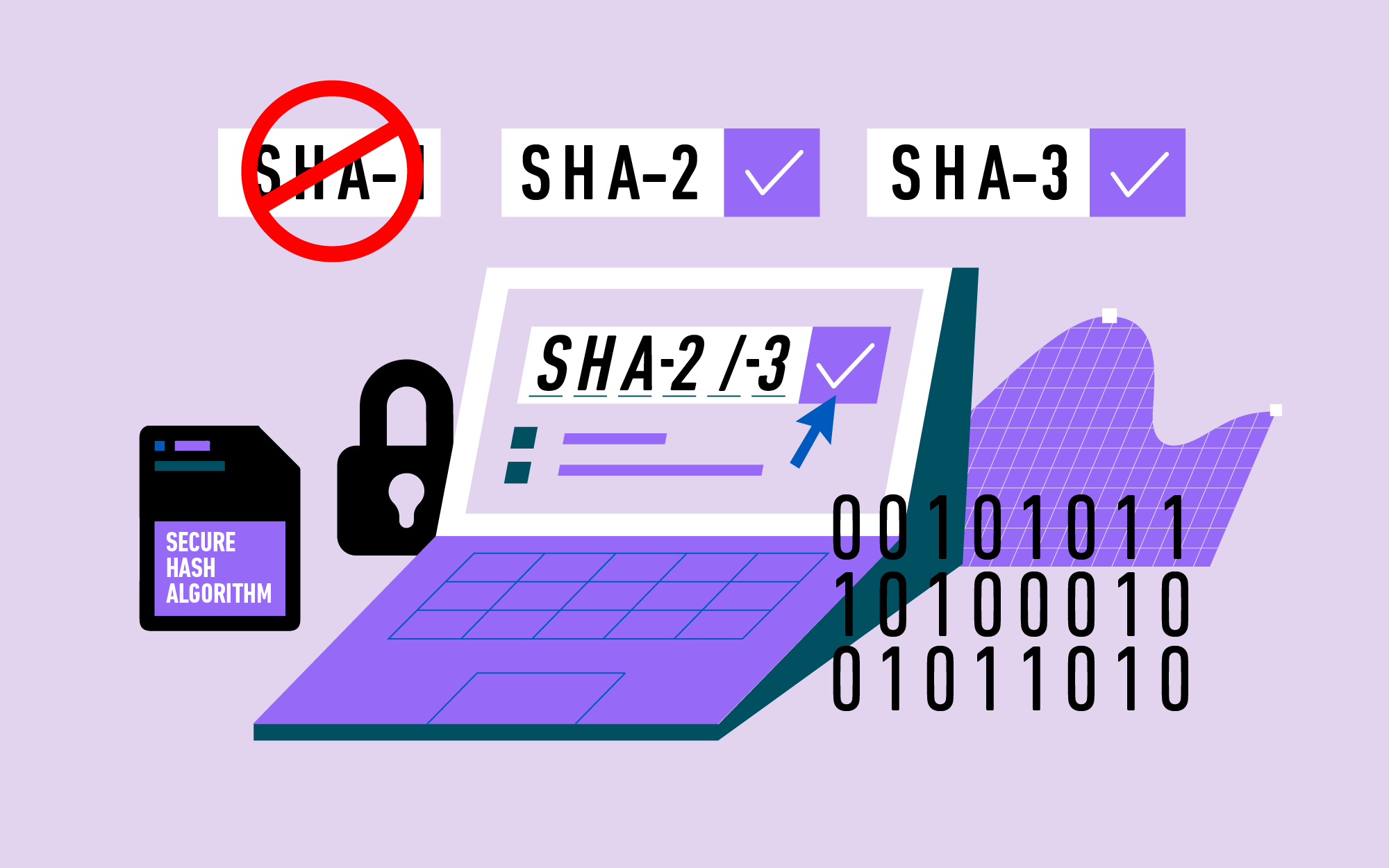

SHA-1 (Secure Hash Algorithm) przestaje być secure. NIST nakazuje