Ancient Iran's 4000-Year Cooling Secret: Air Conditioning's True Roots

Table of Contents

- The Ingenuity of Ancient Persian Climate Control

- Windcatchers (Badgirs): Nature's Air Conditioners

- Qanats: Underground Rivers and Cooling Conduits

- Yakhchals: Masters of Desert Ice Production

- Subterranean Architecture and Courtyard Design

- Beyond Technology: A Holistic Approach to Comfort

- The Enduring Legacy of Ancient Iranian Air Conditioning

- Debunking the Myth: A Deeper Look at "Air Conditioning"

The Ingenuity of Ancient Persian Climate Control

The Persian Empire, a cradle of civilization, stretched across vast, diverse landscapes, many of which were defined by extreme heat. From Mesopotamia to Central Asia, survival and prosperity hinged on the ability to manage the environment. This challenge spurred the development of architectural and engineering solutions that were centuries ahead of their time. The concept of "air conditioning" in ancient Iran was not about mechanically altering air temperature, but rather about manipulating natural elements – wind, water, and earth – to create comfortable indoor environments. This approach was deeply integrated into urban planning and building design, reflecting a profound respect for nature and a sustainable ethos that modern societies are only now beginning to fully appreciate. The sophistication of these systems underscores the ingenuity of ancient Persian climate control.Adapting to the Arid Landscape

Life in the arid landscapes of ancient Iran presented unique and formidable challenges. Summers were brutally hot, with temperatures often soaring well above 40°C (104°F), while water was a precious and scarce commodity. Unlike regions with abundant rainfall, the Persian plateau required innovative solutions not just for water supply but also for managing the intense heat. This harsh reality compelled ancient Persian engineers and architects to think creatively, leading to a symbiotic relationship between building design and environmental conditions. Their adaptations were not mere aesthetic choices but fundamental survival strategies, ensuring that cities could thrive and populations remain healthy despite the unforgiving climate. The core of their strategy revolved around passive cooling – harnessing natural forces rather than expending energy.Windcatchers (Badgirs): Nature's Air Conditioners

Perhaps the most iconic symbol of ancient Iranian air conditioning is the *badgir*, or windcatcher. These tall, elegant structures, often seen crowning traditional Persian homes and buildings, are architectural marvels that harness the power of the wind to cool interiors. Dating back thousands of years, badgirs are a testament to the sophisticated understanding of aerodynamics and thermodynamics possessed by ancient Persian builders. They are, in essence, nature's air conditioners, operating entirely without mechanical parts or external energy input, relying solely on natural principles.Principles of Passive Ventilation

The operation of a badgir is remarkably simple yet highly effective, embodying the principles of passive ventilation. A typical badgir consists of a tower with multiple internal shafts, open to the prevailing winds at the top. The design usually incorporates openings on one or more sides, depending on the direction of the dominant breeze. Here's how they work: * **Catching the Breeze:** When wind blows, it enters the windcatcher's openings. The internal shafts direct this cooler, outdoor air downwards into the building's interior, often into a basement or a central pool. * **Creating a Pressure Differential:** As the cooler air enters, it displaces the warmer, lighter air inside the building. This hot air, being less dense, rises and is expelled through other shafts of the badgir or through strategically placed openings in the building's roof or opposite side. This creates a continuous airflow, effectively ventilating and cooling the space. * **Evaporative Cooling (with water):** Many badgirs were designed in conjunction with a *howz* (small pool) or *qanat* (underground water channel) located in the basement. As the incoming air passes over the cool water, it picks up moisture and cools down through evaporation, similar to a modern swamp cooler. This evaporative cooling significantly enhances the badgir's effectiveness, delivering air that is not only fresh but also noticeably cooler and more humid. * **Drawing Out Hot Air (Stack Effect):** Even on windless days, badgirs can still function. The air inside the tall shaft heats up, becoming less dense and rising, creating a natural "stack effect." This upward movement draws cooler air from lower parts of the building, often from subterranean spaces, or from shaded courtyards, maintaining a continuous, albeit slower, circulation. The design of badgirs varied across regions, adapting to local wind patterns. Some had a single opening facing the prevailing wind, while others had four or eight openings to catch breezes from any direction. The ingenuity of these structures lies in their ability to provide constant, fresh, and cool air, making them a cornerstone of ancient Iranian air conditioning and a model for sustainable architecture.Qanats: Underground Rivers and Cooling Conduits

While windcatchers addressed air circulation, the problem of water scarcity and consistent cooling required another level of genius. This came in the form of the *qanat* (or *karez*), an ancient underground water management system that not only provided a reliable water supply to arid regions but also played a crucial, often overlooked, role in ancient Iranian air conditioning. Qanats are essentially gently sloping underground tunnels that tap into groundwater sources at higher elevations and transport water by gravity to lower-lying areas, sometimes many kilometers away. Their construction, involving vertical shafts dug at intervals to remove excavated material and provide ventilation, was a monumental feat of engineering, requiring immense skill and labor.The Dual Purpose of Water Management

The primary purpose of qanats was, undeniably, water supply for irrigation and domestic use. They allowed agriculture to flourish in deserts and supported the growth of large urban centers where surface water was scarce. However, their design inherently offered a powerful secondary benefit: cooling. Here's how qanats contributed to cooling: * **Stable Subterranean Temperatures:** The water flowing through qanats is consistently cool because it is insulated by the earth. Underground, temperatures remain relatively stable throughout the year, unaffected by the scorching surface heat. This cool water acts as a natural heat sink. * **Evaporative Cooling and Air Circulation:** Many traditional Persian homes and public buildings were built with direct access to a qanat or incorporated underground chambers that intersected with a qanat channel. Air from the building, especially hot air drawn down by a badgir, could be directed to flow over the cool qanat water. As the air passed over the water, it would cool down through evaporation, similar to the principle used in badgirs. * **Cool Air Delivery:** In some designs, specialized shafts or tunnels connected directly from the qanat to living spaces. The cooler, denser air from the qanat tunnel would naturally flow into the warmer building, creating a gentle, constant stream of cool, humidified air. This was particularly effective in subterranean rooms or basements (*sardabs*) which were often built directly above or alongside qanats. * **Humidity Control:** In very dry climates, the evaporative cooling provided by qanats also added much-needed humidity to the air, making the cool air feel even more comfortable and preventing excessive dryness. The combination of qanats and badgirs created a remarkably effective and self-sustaining climate control system. The qanat provided the cool water source and stable underground temperatures, while the badgir facilitated the movement of air, drawing hot air out and pulling cool, qanat-tempered air in. This synergy highlights the holistic approach to ancient Iranian air conditioning, where different technologies worked in concert to maximize comfort.Yakhchals: Masters of Desert Ice Production

Beyond just cooling air and water, ancient Iranians even mastered the art of making and storing ice in the middle of the desert – a feat that seems almost miraculous given the extreme temperatures. This was achieved through the ingenious design of *yakhchals*, or ice houses. These magnificent structures, often conical or domed, stand as enduring monuments to ancient Persian engineering and their sophisticated understanding of thermal dynamics. A yakhchal typically consisted of a large, thick-walled storage chamber, often subterranean, topped by a distinctive conical or domed roof. The walls, made of a unique mortar called *sarooj* (a mixture of sand, clay, egg whites, lime, goat hair, and ash), were incredibly thick, sometimes up to two meters at the base, providing exceptional insulation. The process of making ice involved several clever steps: * **Nighttime Freezing:** During the winter months, shallow pools or channels were constructed on the north side of a high wall, which would cast a permanent shadow. At night, when temperatures dropped significantly (often below freezing in desert winters), water would be channeled into these pools. The combination of radiative cooling to the clear night sky and the low ambient temperatures would cause the water to freeze. * **Ice Harvesting and Storage:** Once frozen, the ice was broken into pieces and transported to the yakhchal's storage chamber. The subterranean nature of the chamber, combined with the massive insulating walls and roof, ensured that the ice remained frozen for extended periods, often well into the scorching summer months. * **Passive Cooling within the Yakhchal:** The conical shape of the yakhchal roof wasn't just for aesthetics; it played a crucial role in its thermal performance. The shape allowed hot air inside the chamber to rise and escape through a small opening at the very top, creating a slight chimney effect. Furthermore, any moisture that evaporated from the ice would condense on the cooler inner surfaces of the dome and drip back down, minimizing ice loss through sublimation. The thick walls prevented heat from penetrating, and the small, often shaded, entrance minimized heat exchange with the outside. Yakhchals provided ancient Iranians with a precious commodity: ice for cooling drinks, preserving food, and even for medical purposes. They represent a pinnacle of ancient Iranian air conditioning, demonstrating an unparalleled ability to manipulate environmental conditions to create comfort and convenience in the most challenging of climates. The existence of these structures, some of which are still standing today, speaks volumes about the advanced scientific and engineering knowledge of the Persian civilization 4000 years ago.Subterranean Architecture and Courtyard Design

Beyond the prominent windcatchers, qanats, and yakhchals, the broader architectural principles employed by ancient Persians were inherently geared towards climate control. The strategic use of subterranean spaces and the ubiquitous courtyard house design formed the backbone of their passive cooling strategy, creating microclimates that offered refuge from the relentless desert sun. This holistic approach to building design was integral to ancient Iranian air conditioning. * **Sardabs (Basements/Underground Rooms):** Many traditional Persian homes featured *sardabs*, or basements, often dug several meters below ground level. The earth itself acts as a massive thermal battery, maintaining a relatively stable temperature throughout the year. By building rooms underground, ancient Persians tapped into this natural coolness. Sardabs were typically the coolest parts of the house during the day, serving as living spaces, sleeping quarters, or storage areas. They were often connected to qanats, allowing cool, humidified air to circulate, or to windcatchers, which would draw air through them. * **Central Courtyards:** The traditional Persian house was typically built around a central courtyard. This design was not merely aesthetic but highly functional for climate control: * **Shade and Microclimate:** The high walls surrounding the courtyard provided deep shade for much of the day, reducing direct solar radiation on the building's exterior. The courtyard itself, often featuring a *howz* (small pool) and lush gardens, created a cooler, more humid microclimate through evaporative cooling from the water and transpiration from plants. * **Air Circulation:** The courtyard acted as a central lung for the house. Hot air rising from the courtyard could create a convection current, drawing cooler air from lower levels or shaded areas into the surrounding rooms. Windcatchers often terminated into the courtyard or adjacent rooms, facilitating this circulation. * **Thermal Mass:** The thick, heavy walls of the buildings, constructed from materials like mud brick, stone, or clay, possessed high thermal mass. This meant they absorbed heat slowly during the day and released it slowly at night. During the day, the walls kept the interior cool by delaying heat transfer. At night, as outdoor temperatures dropped, the stored heat would dissipate, preventing the interior from becoming excessively cold. * **Small, Strategically Placed Openings:** Windows in traditional Persian architecture were typically smaller and fewer in number compared to Western designs, and often recessed or shaded. This minimized direct solar gain and reduced heat transfer from the outside. Openings were carefully positioned to facilitate cross-ventilation when desired, but otherwise to keep the heat out. By combining these elements – subterranean rooms, central courtyards, thick thermal mass walls, and minimal, shaded openings – ancient Persian architects created buildings that were inherently cool and comfortable, showcasing a sophisticated understanding of passive design that formed the bedrock of their "air conditioning" systems.Beyond Technology: A Holistic Approach to Comfort

The genius of ancient Iranian air conditioning extended beyond individual technologies like badgirs or qanats; it encompassed a holistic approach to living that integrated architectural design, urban planning, and daily routines to maximize comfort in challenging climates. This was not merely about engineering solutions but about a way of life that harmonized with the environment. * **Urban Planning and Orientation:** Cities and individual buildings were meticulously planned with climate in mind. Streets were often narrow and winding, providing shade and creating channels for air movement. Buildings were oriented to minimize exposure to the harshest sun, typically with main living areas facing north or shaded courtyards. * **Seasonal Living:** Many traditional homes were designed with different sections for summer and winter living. Summer rooms, often connected to badgirs and qanats, were typically located on the north side of the courtyard or in basements. Winter rooms, designed to capture maximum sunlight, were on the south side. This allowed residents to migrate within their own homes to optimize comfort throughout the year. * **Water Features and Vegetation:** The integration of water features like *howz* (pools) and fountains, along with lush gardens, within courtyards and public spaces was crucial. These elements provided evaporative cooling, increased humidity, and created a psychologically soothing environment. The sound of flowing water also added to the sensory experience of coolness. * **Material Selection:** The choice of building materials, primarily mud brick and plaster, was deliberate. These materials have high thermal mass, meaning they absorb and release heat slowly, effectively buffering indoor temperatures against extreme outdoor fluctuations. Their porous nature also allowed for natural moisture regulation. * **Cultural Practices:** Daily life was also adapted to the climate. Activities were often scheduled to avoid the hottest parts of the day, with siestas common during midday. Even clothing and diet were influenced by the need to stay cool. This comprehensive approach demonstrates that ancient Iranian air conditioning was not just a technological achievement but a cultural one, deeply embedded in the fabric of society. It highlights a sustainable philosophy where comfort was achieved through intelligent design and a deep understanding of natural processes, rather than through energy-intensive mechanical means. The lessons from this holistic approach are profoundly relevant in today's world, urging us to reconsider our relationship with the environment in seeking comfort.The Enduring Legacy of Ancient Iranian Air Conditioning

The innovations in climate control developed by ancient Persians have left an indelible mark on architectural history and continue to inspire modern sustainable design. The principles behind badgirs, qanats, and yakhchals are not just historical curiosities; they are living examples of highly effective, low-energy solutions that predate our current understanding of "green building" by millennia. The legacy of ancient Iranian air conditioning is particularly pertinent in an era grappling with climate change, energy crises, and the urgent need for more sustainable living. * **Inspiration for Modern Architecture:** Contemporary architects and engineers are increasingly looking to traditional passive cooling techniques as models for environmentally responsible design. The principles of natural ventilation (like the stack effect utilized by badgirs), evaporative cooling, and thermal mass are being re-integrated into modern buildings. Architects designing in hot, arid regions, in particular, draw direct inspiration from these ancient methods to reduce reliance on energy-intensive mechanical cooling systems. * **Sustainability and Energy Efficiency:** The ancient Persian systems operated entirely without fossil fuels or electricity. They harnessed renewable resources – wind, water, and the earth's stable temperature – to achieve comfort. This inherent sustainability is a powerful lesson for today's world, where buildings are significant contributors to energy consumption and carbon emissions. The "zero-energy" or "net-zero" building concepts of today find their historical roots in these ancient designs. * **Resilience in a Changing Climate:** As global temperatures rise, the resilience of buildings becomes critical. Passive cooling systems offer inherent resilience against power outages and rising energy costs, providing comfort even when conventional systems fail. The durability and longevity of structures like yakhchals, some of which are thousands of years old, also speak to the quality and robustness of their construction. * **Cultural Heritage and Tourism:** These ancient structures are not just functional but also beautiful, forming a significant part of Iran's rich cultural heritage. They attract tourists and researchers, serving as tangible links to a sophisticated past and offering insights into human adaptation and ingenuity. Many are protected as historical sites, ensuring their preservation for future generations. The enduring legacy of ancient Iranian air conditioning is a powerful reminder that true innovation often lies in understanding and working with nature, rather than against it. These time-tested solutions offer a blueprint for creating comfortable, livable environments that are both ecologically sound and economically viable, proving that the future of cooling might just lie in rediscovering the wisdom of the past.Debunking the Myth: A Deeper Look at "Air Conditioning"

When we speak of "air conditioning" in the context of ancient Iran, it's crucial to clarify that we are not referring to mechanical refrigeration as understood in the 20th century. The modern concept of air conditioning, pioneered by Willis Carrier in the early 1900s, involves complex machinery that uses refrigerants to actively remove heat and humidity from the air, often consuming significant amounts of electricity. This is a fundamentally different process from the passive methods employed by the Persians. The term "air conditioning" itself can be misleading when applied to ancient technologies, as it carries contemporary connotations of mechanical cooling. However, if we define "air conditioning" more broadly as the process of modifying the properties of air (primarily temperature and humidity) to achieve a more comfortable environment, then the ancient Iranian systems absolutely qualify. They were sophisticated, highly effective, and deliberately designed to control indoor climate. * **Passive vs. Active:** The key distinction lies between passive and active systems. Modern AC is *active*, requiring external energy input to run compressors and fans. Ancient Iranian systems were *passive*, relying on natural phenomena like convection, evaporation, and thermal mass. They *conditioned* the air by manipulating natural forces, not by creating artificial ones. * **Efficiency and Scale:** While a single modern AC unit can cool a room quickly and to a precise temperature, ancient systems achieved comfort through continuous, gentle air movement and temperature moderation across entire buildings or even neighborhoods. Their efficiency was measured in sustainability and long-term comfort with minimal resource input, rather than instantaneous cooling power. * **Environmental Impact:** The environmental footprint of ancient Iranian air conditioning was virtually zero. There were no greenhouse gas emissions, no ozone-depleting refrigerants, and minimal energy consumption beyond human labor for construction and maintenance. This stands in stark contrast to the significant environmental impact of modern HVAC systems. Therefore, while the technology was different, the *goal* of ancient Iranian air conditioning was precisely the same as today's: to create a comfortable and livable indoor environment, especially in extreme climates. Recognizing this distinction allows us to appreciate the true genius of these ancient engineers and architects, who achieved remarkable levels of comfort with an unparalleled degree of ecological sensitivity. Their methods offer a profound lesson in how human ingenuity can work in harmony with nature, providing solutions that are both effective and sustainable.Conclusion

The story of ancient Iranian air conditioning, stretching back over 4000 years, is a compelling narrative of human ingenuity, resilience, and a deep understanding of the natural world. From the majestic windcatchers that harnessed the desert breezes to the intricate qanat systems that brought cool water and air underground, and the remarkable yakhchals that produced and preserved ice in scorching heat, these innovations represent a pinnacle of sustainable engineering. They transformed challenging arid landscapes into thriving centers of civilization, proving that comfort and livability do not require energy-intensive technologies. These ancient methods were not mere rudimentary attempts but highly sophisticated, integrated systems that demonstrate a holistic approach to climate control. They remind us that long before the advent of electricity and mechanical refrigeration, humanity found elegant and effective ways to adapt to extreme environments, working with nature rather than attempting to overpower it. The legacy of ancient Iranian "air conditioning" offers invaluable lessons for our present and future, urging us to reconsider our reliance on energy-guzzling solutions and to look back at the timeless wisdom of passive design. We hope this exploration into Iran's 4000-year cooling secret has broadened your perspective on what "air conditioning" truly means. What are your thoughts on these ancient technologies? Do you believe modern architecture can learn more from these sustainable practices? Share your insights in the comments below, or consider sharing this article to spark a conversation about the future of sustainable design!- Does Axl Rose Have A Child

- Seann William Scott S

- Jess Brolin

- How Tall Is Al Pacino In Feet

- Arikystsya Leaked

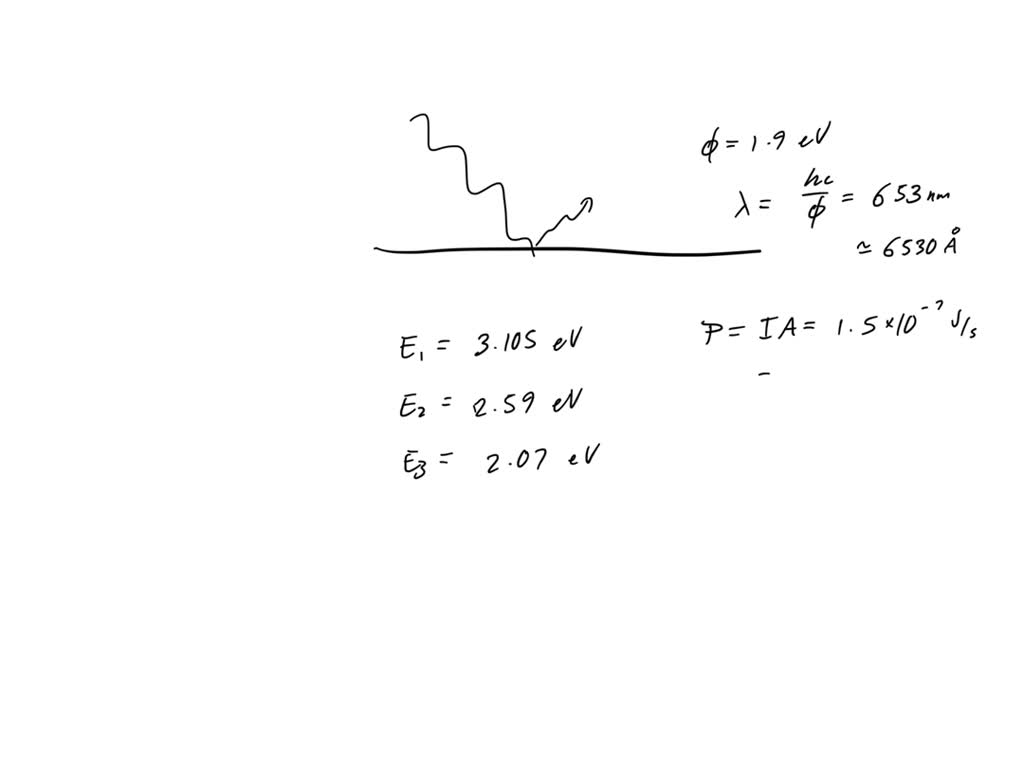

SOLVED: A beam of light consists of four wavelengths: 4000 Ã…, 4800 Ã

Nvidia's RTX 4000 SFF fixes my biggest issue with its GPUs – but there

Buy YAMATIC18 INCH Surface Cleaner for Pressure Washer 4000 PSI