Foucault & The Iranian Revolution: A Contested Legacy Unveiled

Michel Foucault's engagement with the Iranian Revolution stands as one of the most intriguing and hotly debated episodes in the career of the influential French philosopher. His firsthand observations and writings from 1978, at the very zenith of the protests against the Shah of Iran, offered a unique lens through which to view a seismic historical event, yet they simultaneously ignited a storm of controversy that continues to echo in academic circles today. This complex intersection of political upheaval, philosophical inquiry, and cultural interpretation makes the topic of Foucault Iran a fascinating, albeit fraught, area of study.

Far from being a mere historical footnote, Foucault's involvement in Iran challenges us to reconsider the role of the public intellectual, the complexities of non-Western political movements, and the inherent difficulties in interpreting unfolding history. His insights, often misunderstood or deliberately misconstrued, provide a crucial, if contentious, perspective on a revolution that reshaped the geopolitical landscape and continues to influence global discourse on religion, power, and social change. Unpacking this legacy requires a careful navigation of Foucault's original intentions, the historical context, and the subsequent critical interpretations that have shaped our understanding.

Table of Contents

- Michel Foucault: A Brief Intellectual Portrait

- The Genesis of Foucault's Iranian Interest

- Witnessing a "Political Spirituality"

- Foucault's Critique of the Shah's Regime

- The Contested Legacy: Debates and Criticisms

- The Enduring Mark on Foucault's Thought

- Modern Scholarship and Reinterpretations

- Why Foucault's Iran Engagement Still Matters

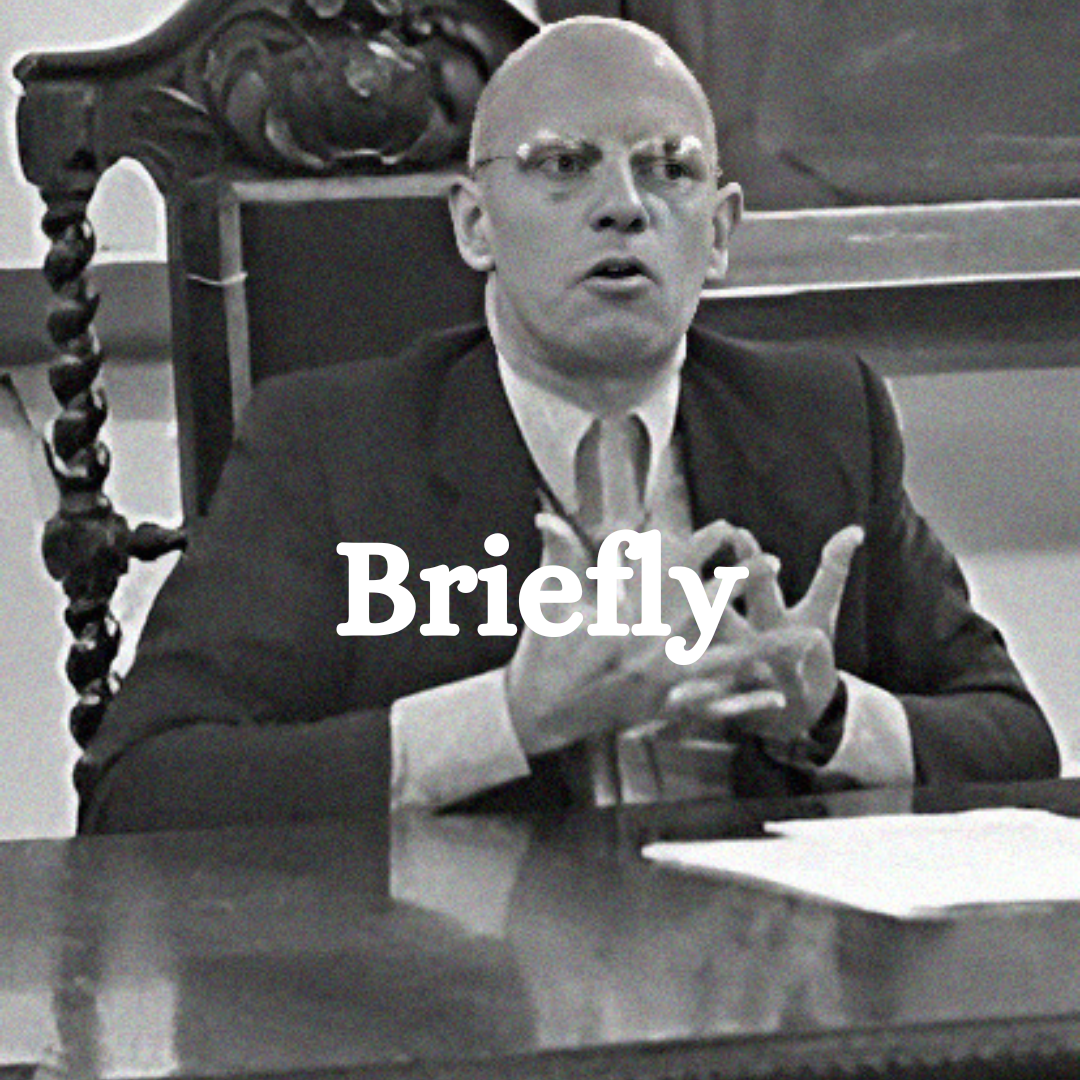

Michel Foucault: A Brief Intellectual Portrait

Before delving into the specifics of Foucault's involvement with the Iranian Revolution, it's essential to briefly situate the man himself. Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a towering figure in 20th-century French thought, whose work profoundly influenced fields ranging from philosophy and history to sociology and literary criticism. Known for his groundbreaking analyses of power, knowledge, discourse, and institutions, Foucault challenged conventional understandings of madness, punishment, sexuality, and the very construction of the human subject.

- Seann William Scott S

- Malia Obama Dawit Eklund Wedding

- Vegas Foo

- Brennan Elliott Wife Cancer

- Arikytsya Of Leaks

His methodologies, often described as "archaeological" and "genealogical," sought to uncover the historical conditions and power dynamics that shaped various forms of knowledge and social practices. Foucault was not merely an academic; he was also a politically engaged intellectual, often participating in protests and advocating for marginalized groups. This blend of rigorous scholarship and active political commitment set the stage for his controversial foray into the unfolding events in Iran.

Personal Data & Key Milestones

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Paul-Michel Foucault |

| Born | October 15, 1926, Poitiers, France |

| Died | June 25, 1984, Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma Mater | École Normale Supérieure (Paris) |

| Key Fields | Philosophy, History of Ideas, Social Theory, Literary Criticism |

| Notable Works | Madness and Civilization, Discipline and Punish, The History of Sexuality |

| Key Concepts | Power/Knowledge, Discourse, Biopower, Panopticism, Genealogy, Archaeology |

| Role in Iran (1978) | Special Correspondent for Corriere della Sera and Le Nouvel Observateur |

The Genesis of Foucault's Iranian Interest

Foucault’s interest in Islamism and the unfolding events in Iran started in 1978. As the protests against the Shah of Iran reached their zenith, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera called on him to write a series of articles about Iran. This opportunity positioned him not as a detached academic observer, but as a special correspondent, offering him direct access to the revolutionary fervor gripping the nation. He also contributed to the French publication Le Nouvel Observateur.

In 1978, a storm of anger had indeed swept across the ancient land of Iran, casting long shadows over the aging regime of the Shah, whose reign, deeply imbued with the colors of Westernization, was already showing signs of fragility. Foucault arrived at a pivotal moment, witnessing a society on the brink of profound transformation. His journalistic reports, later compiled and translated, offer a raw, immediate account of the revolution as it unfolded, providing invaluable primary source material for understanding Foucault's perspective on this complex historical phenomenon.

Witnessing a "Political Spirituality"

What Foucault discovered in Iran was, in his words, a "political spirituality." This was a concept that resonated deeply with his philosophical interests in power and resistance. He observed a mass mobilization on this earth modeled on the coming of a new Islamic vision of social forms of coexistence and equality. Foucault described the mass mobilization in Iran as an Islamic uprising, emphasizing the unique blend of religious fervor and political aspiration that characterized the movement.

For Foucault, this "political spirituality" was not merely a return to tradition, but a novel form of collective will and agency that defied conventional Western political categories. He was intrigued by the idea of a people willing to risk everything, even their lives, for a spiritual ideal that translated directly into political action. This was a stark contrast to the secular, rationalized political movements he was accustomed to analyzing in the West. His observations suggested a form of resistance that drew its strength from a collective desire for a different kind of social order, one rooted in shared spiritual convictions rather than purely economic or material grievances.

Beyond Western Binaries

Foucault's approach to the Iranian Revolution sought to go beyond simple binaries. He aimed to avoid the clichéd vocabulary often used by progressivists to describe these events—or to criticize Foucault for his alleged naivety. He was attempting to understand a phenomenon on its own terms, rather than force it into pre-existing Western frameworks of revolution or modernization. This intellectual honesty, while admirable to some, became a major point of contention for others who felt he was overlooking the darker implications of the emerging Islamist movement.

His fascination lay in the emergence of a collective will that transcended traditional political structures. He saw in the Iranian uprising a profound spiritual dimension that gave it immense power and coherence. This perspective, however, led to accusations that he was romanticizing the revolution or failing to foresee the authoritarian nature of the future Islamic Republic. The complexity of his observations, therefore, remains a subject of intense debate, highlighting the challenge of interpreting rapidly evolving political landscapes without the benefit of hindsight.

Foucault's Critique of the Shah's Regime

While often remembered for his controversial embrace of the revolution's spiritual dimension, Foucault also offered a sharp critique of the Shah's regime. He devoted much of his introductory discussion to the army's organizational structure and its function in modern Iranian history. In sharp contrast to the valiant patriotic role played by national armies in Latin America's wars of independence, Foucault rather snidely noted, the Iranian army has never liberated a thing. This pointed observation highlighted the army's role as an instrument of internal repression and a prop for the Shah's autocratic rule, rather than a force for national liberation or defense.

His writings painted a picture of a regime that, despite its Westernizing façade, was deeply unpopular and relied heavily on coercion. The Shah's rule, "impregnated with the colors of Westernization," as one contemporary observer noted, showed clear signs of fragility. Foucault's analysis of the army, coupled with his understanding of the popular discontent, provided a critical backdrop against which the "political spirituality" of the revolution could be understood as a genuine popular uprising against an oppressive and unrepresentative state.

The Contested Legacy: Debates and Criticisms

Foucault's engagement with the Iranian Revolution remains a contested aspect of his intellectual legacy, sparking debates about the intersections of political activism, philosophy, and cultural interpretation. The issue of Foucault's involvement in Iran is still a relatively unexplored theme in Foucault research and one that is actually bypassed by the majority of Foucault scholars, since the general view is that it was a breathtaking mistake, comparable to Heidegger's flirtation with National Socialism.

This harsh comparison to Martin Heidegger's support for Nazism underscores the severity of the criticism leveled against Foucault. Critics argue that he failed to adequately assess the potential for authoritarianism within the Islamist movement, or that his philosophical framework led him to romanticize a movement that would ultimately suppress individual liberties and human rights. His famous quote, "Non so fare la storia del futuro e sono un po’ maldestro a prevedere il passato" (I don't know how to make the history of the future and I'm a bit clumsy at predicting the past), often cited in defense of his position, highlights his reluctance to predict outcomes, yet it does little to assuage those who believe he should have been more discerning.

Echoes of Heidegger?

The comparison to Heidegger is particularly damaging because it implies a fundamental moral or intellectual failing. While Foucault's critics acknowledge that he did not endorse the subsequent abuses of the Islamic Republic, they contend that his initial enthusiasm or perceived lack of critical distance was a serious misjudgment. They argue that a philosopher of Foucault's stature should have been more vigilant against the dangers of a populist movement that could quickly turn repressive. This debate is central to understanding the enduring controversy surrounding Foucault Iran.

However, it's also important to note that this comparison is often made with the benefit of hindsight. Foucault was observing a revolution in real-time, without knowing its ultimate trajectory. The challenge for scholars is to analyze his writings within that immediate context, while also acknowledging the subsequent historical developments that inevitably color our retrospective judgments.

Re-evaluating the Discourse

Some contemporary analyses of Foucault's work on Iran attempt to move beyond these simplistic condemnations. For instance, the book Foucault and the Iranian Revolution, while containing translations of Foucault’s writings on Iran in its appendix (which is noted as its only redeeming quality), is also criticized because the rest of the book is truly a testament to how the rhetoric of fear that has defined US foreign policy since September 11 has even reshaped the discourse of the intellectual left. This critique suggests that much of the condemnation of Foucault's stance is itself influenced by later geopolitical narratives, rather than a pure engagement with his original texts.

Similarly, another work, Gender and the Seductions of Islamism (©2005), while perhaps not directly about Foucault, highlights the complex interplay of factors at play during the revolution. It reminds us that simplistic interpretations often fail to capture the nuanced realities of such events. A "splendid work that goes beyond simple binaries," it has no sympathy for the clichéd vocabulary used by progressivists to describe these events—or to criticize Foucault for his alleged naivety. This perspective suggests that Foucault's attempt to avoid "clichéd vocabulary" was precisely what made his analysis unique, even if it proved to be controversial.

The Enduring Mark on Foucault's Thought

Despite the controversies, Foucault in Iran centers not only on the significance of the great thinker’s writings on the revolution but also on the profound mark the event left on his later work. His experience in Iran, witnessing a collective will manifest through a "political spirituality," undoubtedly influenced his evolving understanding of power, resistance, and the formation of subjectivity. It pushed him to consider forms of power and resistance that operated outside the traditional Western models he had previously analyzed.

The Iranian Revolution, with its unique blend of religious authority and popular uprising, challenged Foucault to expand his conceptual toolkit. It forced him to confront a situation where power was not solely exercised through state apparatuses or disciplinary institutions, but also through spiritual and communal bonds. This encounter with a non-Western political phenomenon enriched his later work, particularly his exploration of ethics and the "care of the self," as he grappled with how individuals and communities might constitute themselves outside of dominant power structures.

Modern Scholarship and Reinterpretations

Almost forty-five years have passed since that revolution against the Shah that Michel Foucault recounted firsthand in articles and interviews. These writings are now finally collected in Italian in a single volume, Dossier Iran (edited by Sajjad Lohid), along with other unpublished documents. This compilation, curated by the scholar of Iranian origins Sajjad Lohi for the Italian public, brings together for the first time both the journalistic reports written by the philosopher and other essential texts. Such efforts demonstrate a renewed interest in comprehensively understanding Foucault's original contributions, moving beyond selective interpretations.

These recent compilations and scholarly works aim to provide a more complete picture of Foucault's engagement, allowing researchers to delve into the nuances of his observations rather than relying on secondhand accounts or politically charged critiques. By making his full body of work on Iran accessible, contemporary scholarship seeks to re-evaluate his contributions and understand the complexities of his thought in the context of the revolution, fostering a more informed debate on Foucault Iran.

Why Foucault's Iran Engagement Still Matters

The enduring relevance of Foucault's engagement with the Iranian Revolution extends beyond mere academic curiosity. It serves as a potent reminder of the challenges inherent in interpreting complex global events, especially those driven by non-Western paradigms. His experience highlights the pitfalls of applying universal frameworks to diverse cultural and political contexts, and the necessity of listening to voices and movements on their own terms, even when their trajectories are uncertain or ultimately undesirable.

Furthermore, the debates surrounding Foucault Iran force us to reflect on the responsibility of intellectuals in times of political upheaval. How does one balance critical analysis with empathetic understanding? When does observation become endorsement? These are not easy questions, and Foucault's controversial foray into the Iranian Revolution provides a rich case study for grappling with them. By revisiting this chapter of his intellectual life, we gain not only a deeper understanding of Foucault himself but also invaluable insights into the enduring complexities of revolution, power, and the ever-shifting landscape of global politics.

In conclusion, Michel Foucault's direct involvement in the Iranian Revolution was a pivotal, albeit contentious, moment in his intellectual journey. His concept of "political spirituality" offered a unique perspective on the mass mobilization against the Shah, challenging Western analytical frameworks. While his observations have drawn significant criticism, often comparing his misjudgment to Heidegger's political failings, recent scholarship seeks to provide a more nuanced understanding of his original writings, moving beyond post-9/11 rhetoric and simplistic binaries.

The story of Foucault Iran is a testament to the complexities of history and the fraught role of the intellectual. It invites us to engage with difficult questions about power, resistance, and interpretation. What are your thoughts on Foucault's observations? Share your perspective in the comments below, or explore other articles on our site that delve into the intersections of philosophy and political history.

Foucault in Iran, 1978-1979 - AOSIS

Michel Foucault

Dwayne Johnson | Michel Foucault | Know Your Meme