Decoding Foucault's Iran: A Philosopher's Controversial Journey

The intellectual landscape of the late 20th century was profoundly shaped by figures like Michel Foucault, whose incisive critiques of power, knowledge, and institutions resonated globally. Yet, few episodes in his illustrious career have sparked as much debate and controversy as his engagement with the Iranian Islamic Revolution. On the eve of this momentous event, Foucault traveled to Iran twice, penning eight reports for the *Corriere della Sera* newspaper that revealed a deep sympathy for the revolutionary people of Iran and an unexpected praise for their Islamic Revolution. This period of Foucault's intellectual journey, often overlooked or oversimplified, offers a fascinating lens through which to examine the complexities of political change, the allure of revolutionary fervor, and the challenges of interpreting historical events through a philosophical framework.

His writings from Iran, initially met with a mix of fascination and skepticism, have since become a touchstone for understanding not only Foucault's evolving thought but also the broader intellectual responses to the rise of Islamism. The originality of works that link Foucault's main ideas to the Iranian Revolution lies precisely in their ability to illuminate one through the other, offering fresh perspectives on both the philosopher's concepts and the revolution's multifaceted nature. This article delves into Foucault's controversial encounter with Iran, exploring his insights, the criticisms he faced, and the enduring legacy of his "Iranian writings."

Table of Contents

- Michel Foucault: A Brief Intellectual Biography

- The Context: Iran on the Brink of Revolution (1978)

- Foucault's Encounters with the Iranian Revolution

- "Political Spirituality": Foucault's Controversial Insight

- The Global Left, Islamism, and Foucault's Position

- Critiques and Defenses of Foucault's Iran Writings

- "Foucault in Iran" and "Foucault and the Iranian Revolution": Academic Perspectives

- Conclusion: Foucault's Iranian Legacy

Michel Foucault: A Brief Intellectual Biography

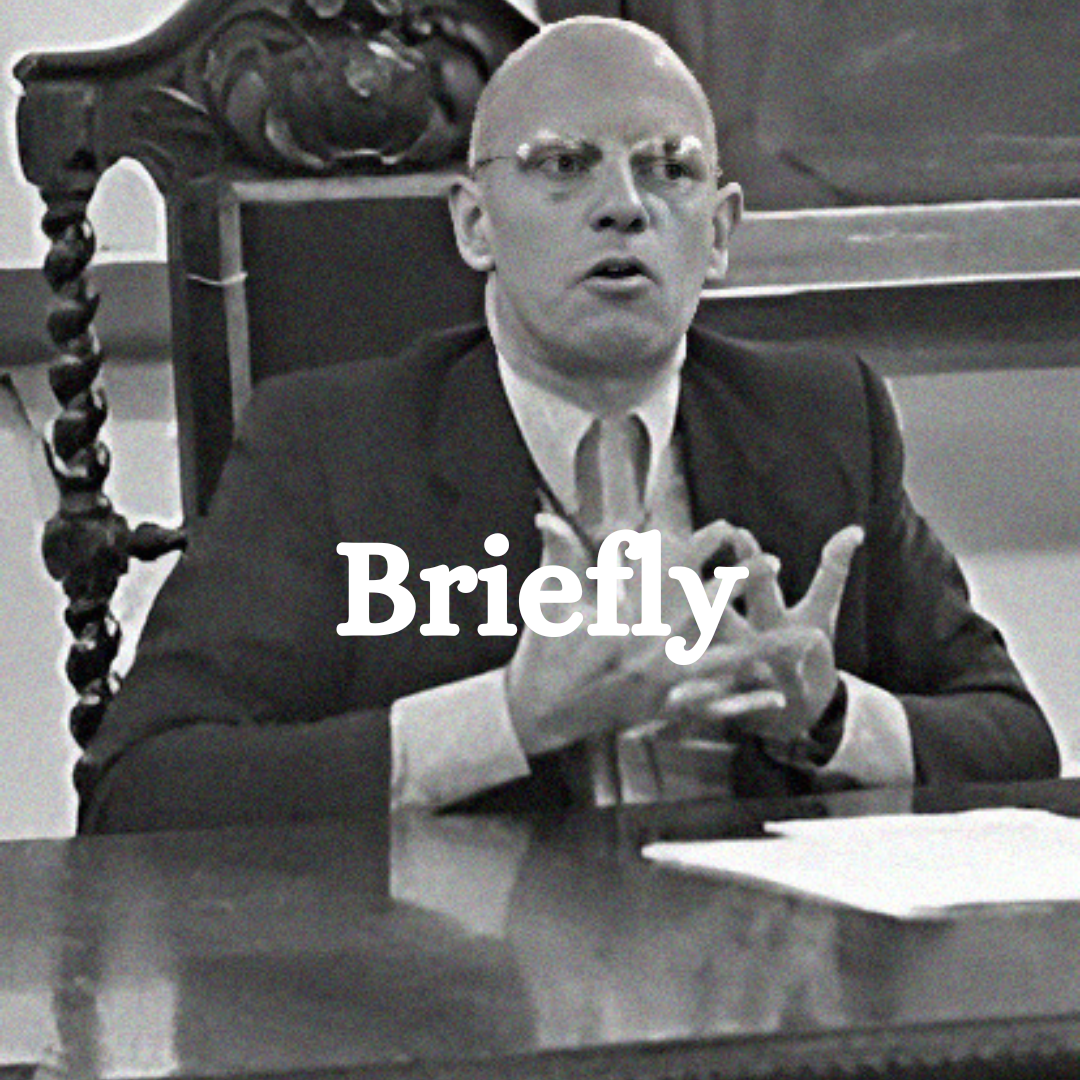

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a towering figure in 20th-century French thought, whose work spanned philosophy, history, sociology, and critical theory. At the time of his visits to Iran, Foucault was an esteemed professor at the Collège de France, recognized globally for his incisive critiques of historical and social institutions. His methodologies, often termed "archaeology" and "genealogy," sought to uncover the hidden power structures embedded within discourse, knowledge systems, and social practices. Foucault's intellectual journey was characterized by a relentless questioning of established norms, particularly concerning power dynamics in prisons, asylums, and medical institutions.

- Averyleigh Onlyfans Sex

- Jameliz Onlyfans

- Photos Jonathan Roumie Wife

- Jonathan Roumie Partner

- Allmobieshub

Beyond his academic pursuits, Foucault was also deeply engaged with various social and political movements. Notably, he was a key figure in the *Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons* (GIP), a prisoners' rights movement he co-founded in the early 1970s. This engagement with the realities of incarceration and state power gave him a unique perspective on resistance and human agency, which would profoundly influence his observations in Iran. His commitment to understanding power from the ground up, from the perspective of the marginalized and oppressed, positioned him to view the burgeoning revolution in Iran not merely as a political upheaval but as a profound societal transformation.

Personal Data & Key Milestones

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Paul-Michel Foucault |

| Born | October 15, 1926, Poitiers, France |

| Died | June 25, 1984, Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | École Normale Supérieure, University of Paris (Sorbonne) |

| Notable Works | *Madness and Civilization*, *The Order of Things*, *Discipline and Punish*, *The History of Sexuality* |

| Key Ideas | Power/Knowledge, Discourse, Genealogy, Archaeology, Biopower, Panopticism |

| Academic Role | Professor at Collège de France (Chair of History of Systems of Thought) |

The Context: Iran on the Brink of Revolution (1978)

The year 1978 marked a critical turning point in Iranian history. Protests against the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had reached their zenith, fueled by widespread discontent over political repression, economic disparities, and the perceived Westernization of Iranian society. The Shah's authoritarian rule, coupled with his ambitious modernization programs, had alienated significant segments of the population, including the traditional clergy, intellectuals, and the urban poor. This volatile environment created a fertile ground for revolutionary change, with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled in Paris, emerging as a charismatic leader who galvanized the opposition.

It was amidst this escalating crisis that Foucault's attention was drawn to Iran. In 1977, two French lawyers, who were actively involved in Iranian exilic politics, brought the issue of Iranian political prisoners to his attention. Given Foucault's long-standing commitment to prisoners' rights through his work with the GIP, this appeal resonated deeply with him. This initial connection opened the door for him to visit Iran and witness the revolution firsthand. Working as a special correspondent for prominent European newspapers, *Corriere della Sera* and *Le Nouvel Observateur*, Foucault was uniquely positioned not just to observe but to reflect philosophically on the unfolding events, providing a perspective that diverged sharply from conventional Western analyses.

- Marietemara Leaked Vids

- Shagle

- Daisy From Dukes Of Hazzard Now

- Terry Mcqueen

- Sophie Rain Spiderman Video Online

Foucault's Encounters with the Iranian Revolution

Michel Foucault's direct engagement with the **Iranian Revolution** unfolded during two crucial visits to the country in 1978. These trips were not mere journalistic assignments; for Foucault, they represented an opportunity to witness a unique form of political mobilization and to explore the emergence of a new kind of collective will. In the eight reports he subsequently wrote for *Corriere della Sera*, Foucault showed deep sympathy with the revolutionary people of Iran and praised their Islamic Revolution, a stance that would later become a source of significant controversy.

What Foucault discovered in Iran was, in his words, a "political spirituality." This concept was central to his interpretation of the mass mobilization he observed. He described it as an "Islamic uprising," characterized by a profound collective desire for a new social order. He saw it as "a mass mobilization on this earth modeled on the coming of a new Islamic vision of social forms of coexistence and equality." This was not, for Foucault, merely a political coup or a power struggle, but a spiritual and existential transformation. He was fascinated by the idea that an entire populace could be driven by a shared, almost mystical, aspiration to redefine their collective existence outside the conventional frameworks of Western political thought. This emphasis on spirituality and collective will, rather than economic or class-based analysis, set his observations apart and made them particularly challenging for many of his contemporaries to comprehend.

"Political Spirituality": Foucault's Controversial Insight

The concept of "political spirituality" is arguably the most enduring and contentious aspect of Foucault's writings on the **Iranian Revolution**. Foucault was, unfortunately, precisely seduced by the popular uprising in Iran, which he claimed might signify a new "political spirituality," with the potential to transform the political landscape of Europe, as well as the Middle East. For a philosopher who had spent years dissecting the mechanisms of power and control in Western societies, the Iranian phenomenon offered a stark contrast—a collective will seemingly unconstrained by traditional political structures, driven instead by a shared, transcendent purpose.

Foucault saw in the Iranian people's willingness to face death for their cause not a fanatical adherence to dogma, but a profound commitment to an ideal that transcended individual interests. This "political spirituality" was, for him, a challenge to the secular, rationalist paradigms that had dominated Western political thought since the Enlightenment. He was intrigued by the idea that a religious framework could serve as the bedrock for a mass mobilization aimed at creating "new Islamic vision of social forms of coexistence and equality." This fascination, however, led him to perhaps overlook or downplay the authoritarian potential inherent in such a movement, a point that his critics would later seize upon. His emphasis on the spiritual dimension, while philosophically provocative, also made his analysis vulnerable to accusations of naiveté regarding the political realities that would soon unfold in post-revolutionary Iran.

The Global Left, Islamism, and Foucault's Position

The Islamic Revolution in Iran, which brought Islamists to power for the first time in modern history, created a significant ideological rift, effectively pitting the global left—perhaps best personified by Michel Foucault—against the global right. For many on the left, the revolution presented a complex dilemma. While they might have sympathized with the anti-imperialist and anti-Shah sentiments, the religious character of the revolution and its subsequent authoritarian turn challenged their secular and progressive ideals. Foucault's embrace of the revolution, even if nuanced, placed him firmly on one side of this divide, making his work a focal point for subsequent debates.

His writings on Iran became a battleground for intellectual discourse, reflecting broader anxieties about the rise of Islamism and its implications for Western political thought. The very idea that a leading Western philosopher could find something admirable, or at least profoundly interesting, in a religious revolution was unsettling to many. This tension underscores the enduring relevance of Foucault's "Iran writings" in understanding the complex relationship between Western intellectual traditions and the political movements of the Global South, particularly those rooted in religious identity.

Foucault's Influence on Debates on Islamism and Iran

As Azar Nafisi, author of *Reading Lolita in Tehran*, aptly notes, "The authors remind us of Foucault's immense influence in the current debates on Islamism and Iran." The book's originality, she suggests, "lies in the way it links Foucault's main ideas to the Iranian Revolution, thereby illuminating one through the other." This highlights how Foucault's engagement with Iran continues to shape contemporary discussions. His concepts of power, resistance, and the formation of subjectivity offer tools for analyzing the dynamics of Islamist movements, even if his initial interpretations of the revolution proved controversial.

Foucault's work prompts us to look beyond simplistic binaries and consider the internal logic and aspirations of such movements, rather than dismissing them outright as irrational or oppressive. While his early optimism about the revolution's "political spirituality" might seem misplaced in hindsight, his attempt to understand it on its own terms, rather than through a pre-conceived Western framework, remains a valuable, albeit challenging, intellectual exercise. This approach encourages a deeper, more nuanced engagement with the complexities of Islamism and its historical trajectory, moving beyond mere condemnation to a more profound analysis of its origins and appeal.

Critiques and Defenses of Foucault's Iran Writings

Michel Foucault's enthusiastic early reports on the **Iranian Revolution** quickly came under increasing attack. By March 1979, in the wake of the new regime's executions, the criticisms intensified. Many scholars and commentators charged Foucault with having endorsed Islamist violence by supporting the revolution, arguing that his philosophical lens had blinded him to the oppressive realities that would soon emerge. This was a scathing critique, accusing a philosopher known for his critiques of power of seemingly endorsing a new form of authoritarianism.

One notable critic was Maxime Rodinson, who, as later revealed, was specifically targeting Foucault in his articles. Rodinson drew on Max Weber’s notion of charisma, Marx’s concepts of class and ideology, and a range of scholarship on Iran and Islam to counter Foucault's interpretation. He argued that Foucault's focus on "political spirituality" was insufficient to grasp the socio-economic and political forces at play, which, in his view, inevitably led to a new form of state control. The intellectual debate surrounding Foucault's Iran writings became a microcosm of the broader ideological struggles of the time, reflecting deep divisions within the global left regarding the nature of revolution and the role of religion in politics.

Interpreting Foucault: Humanism, Liberalism, or Naiveté?

Foucault's defenders interpret the Iran writings as his movement toward humanism and liberalism, a reorientation, they argue, that ought to absolve Foucault from guilt in the case of Iran. This perspective suggests that Foucault was genuinely seeking a new form of political emancipation, and his initial enthusiasm was a reflection of this search, rather than an endorsement of future repression. They contend that his observations were made at a specific, fluid moment in the revolution, and his subsequent silence or withdrawal from the topic after the executions indicated a recognition of the shift in the regime's character.

Furthermore, some argue that a "splendid work that goes beyond simple binaries, it has no sympathy for the clichéd vocabulary used by progressivists to describe these events—or to criticize Foucault for his alleged" naiveté. This view posits that Foucault was attempting to understand a phenomenon that defied easy categorization within Western political thought, and his "seduction" by the popular uprising was a testament to his intellectual courage in confronting the unknown. However, others maintain that Foucault, unfortunately, was precisely seduced by the popular uprising in Iran, which he claimed might signify a new "political spirituality," with the potential to transform the political landscape of Europe, as well as the Middle East. This latter view suggests that his philosophical predispositions led him to an overly optimistic, and ultimately misguided, assessment of the revolution's true nature.

"Foucault in Iran" and "Foucault and the Iranian Revolution": Academic Perspectives

Over three decades after his death and almost four decades after his visits, Foucault's intellectual journey to Iran continues to be a subject of rigorous academic inquiry. Two notable works, "Foucault in Iran" and "Foucault and the Iranian Revolution," offer distinct perspectives on this controversial period. "Historically rich and theoretically nuanced, Foucault in Iran advances a scathing critique of previous works on this subject that charged Foucault with having endorsed Islamist violence by supporting the revolution." This indicates a scholarly effort to move beyond simplistic condemnations and engage with the complexity of Foucault's thought and the historical context.

In contrast, "Foucault and the Iranian Revolution's only redeeming quality is that it contains translations of Foucault's writings on Iran in its appendix." The rest of the book, according to some critiques, "is truly a testament to how the rhetoric of fear that has defined US foreign policy since September 11 has even reshaped the discourse of the intellectual left." This suggests that some analyses of Foucault's Iran writings have been influenced by later geopolitical developments, potentially distorting the historical context of Foucault's original observations. Michiel Leezenberg, who teaches in the philosophy and religious studies departments of the University of Amsterdam and has published numerous articles on the social and intellectual history of the Islamic world, offers valuable insights into this complex interplay of philosophy, history, and geopolitics, underscoring the ongoing relevance of Foucault's engagement with Iran.

Beyond Simple Binaries: Nuance in Understanding

The academic discourse surrounding Foucault's engagement with the **Iranian Revolution** highlights the imperative to move beyond simple binaries. It is tempting to label Foucault as either a prescient observer or a naive idealist, but such categorizations fail to capture the profound intellectual challenge that the revolution posed to his philosophical framework. His Iran writings are not merely a historical curiosity but a case study in how a leading intellectual grappled with a phenomenon that defied conventional Western political analysis.

The debates surrounding his work underscore the difficulty of interpreting events in real-time, especially when they challenge deeply held assumptions about progress, secularism, and political agency. Understanding Foucault's perspective requires acknowledging the specific historical moment of his visits, the revolutionary fervor that captivated him, and his genuine intellectual curiosity about new forms of collective action and "political spirituality." This nuanced approach allows us to learn not only about Foucault's evolving thought but also about the enduring complexities of the Iranian Revolution itself and its far-reaching implications for global politics and intellectual discourse.

Conclusion: Foucault's Iranian Legacy

Michel Foucault's engagement with the Iranian Islamic Revolution remains one of the most intriguing and contentious chapters in his intellectual biography. His two trips to Iran in 1978, and the subsequent reports for *Corriere della Sera*, revealed a philosopher deeply sympathetic to the revolutionary people and captivated by what he termed "political spirituality"—a mass mobilization driven by an Islamic vision of social forms of coexistence and equality. This perspective, while initially praised by some, quickly drew sharp criticism, particularly after the new regime's executions in 1979, with many accusing Foucault of endorsing Islamist violence or being dangerously naive.

Yet, the enduring power of Foucault's Iran writings lies not in their predictive accuracy, but in their capacity to provoke thought and challenge conventional understandings. As Azar Nafisi noted, the link between Foucault's ideas and the Iranian Revolution continues to illuminate both. Whether interpreted as a move towards humanism and liberalism, or as a problematic seduction by revolutionary fervor, his observations force us to confront the complexities of religious movements, the limits of Western political thought, and the profound, often unpredictable, nature of social change. The academic scrutiny, from "Foucault in Iran"'s nuanced critique to "Foucault and the Iranian Revolution"'s more polemical stance, underscores the lasting impact of this brief but intense period in Foucault's life.

Foucault's journey to Iran serves as a powerful reminder that history and philosophy are intertwined, and that understanding global events requires a willingness to engage with perspectives that defy easy categorization. His legacy encourages us to look beyond simple binaries and to delve into the intricate layers of political and spiritual aspirations that drive human action. We invite you to share your thoughts on Foucault's controversial encounter with Iran in the comments below. How do you interpret his concept of "political spirituality"? What lessons can we draw from his experience regarding the role of intellectuals in revolutionary times? Explore more articles on philosophy, history, and geopolitics on our site to continue this fascinating intellectual journey.

- Abby And Brittany Hensel Died

- Brennan Elliott Wife Cancer

- Rob Van Winkle

- Faith Jenkins Net Worth 2024

- Yessica Kumala

Foucault in Iran, 1978-1979 - AOSIS

Michel Foucault

Dwayne Johnson | Michel Foucault | Know Your Meme