Did Reagan Know? Unraveling The Iran-Contra Mystery

The question of whether Ronald Reagan knew about the illicit arms-for-hostages deal known as Iran-Contra remains one of the most enduring and contentious mysteries in American political history. This complex scandal, which unfolded during his second term, cast a long shadow over an otherwise popular presidency, raising serious questions about executive power, accountability, and the rule of law. The implications of such a high-level covert operation, seemingly in defiance of congressional mandates, continue to fuel debate among historians, political scientists, and the public.

Decades later, the debate persists: was the "Teflon President" genuinely unaware of the illegal activities carried out by his administration, or was he complicit in a scheme that violated congressional mandates and international norms? While official reports often stated there was "no evidence Reagan knew his claim was false," a closer look at the available information, the testimonies, and the political climate of the era suggests a more nuanced and unsettling picture. This article delves into the intricate web of evidence, denials, and investigations to explore the depths of the Iran-Contra affair and the enduring question of presidential knowledge, particularly focusing on the crucial inquiry: did Reagan know about Iran-Contra?

Table of Contents

- The Iran-Contra Affair: A Brief Overview

- Ronald Reagan: A Biographical Sketch

- The Core of the Controversy: Presidential Knowledge

- Congressional Investigations and Their Findings

- The Legacy of Iran-Contra and Presidential Power

- The Nicaragua Connection: Context and Strategy

- The Bush Factor: A Successor's Shadow

- Conclusion: An Enduring Question

The Iran-Contra Affair: A Brief Overview

The Iran-Contra affair was a political scandal in the United States that came to light in November 1986. It involved the clandestine sale of arms to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages held in Lebanon, and the diversion of the profits from these sales to fund the Contras, a rebel group fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. This operation directly violated the Boland Amendment, a series of legislative amendments passed by the U.S. Congress that aimed to limit U.S. government assistance to the Contras. The intricate scheme saw the U.S. circumventing its own laws and public policy. As the details emerged, it became clear that "The Americans got around this by selling weapons to Israel instead. Israel would then sell the weapons to Iran secretly, in exchange for the release of American hostages being held by an extremist terrorist group in neighbouring Lebanon that supported the new Iranian government (who promptly took new hostages)." This elaborate workaround highlighted the administration's determination to pursue its objectives, even if it meant operating outside the bounds of established legal frameworks. The affair was a stark example of executive overreach and a secret foreign policy conducted without congressional oversight, raising immediate questions about who knew what and when, particularly regarding President Reagan's involvement.Ronald Reagan: A Biographical Sketch

Ronald Wilson Reagan, the 40th President of the United States, was a towering figure in American politics, often credited with revitalizing the conservative movement and ending the Cold War. Born in Tampico, Illinois, in 1911, Reagan initially gained prominence as a Hollywood actor, starring in over 50 films. His charisma and communication skills, honed during his acting career, would later become hallmarks of his political persona, earning him the moniker "The Great Communicator." Reagan transitioned into politics relatively late in life, becoming a prominent conservative voice and eventually serving as the Governor of California from 1967 to 1975. His presidency, from 1981 to 1989, was marked by a strong anti-communist stance, significant tax cuts, and a push for deregulation, often encapsulated by the term "Reaganomics." While he championed a vision of smaller government, it's notable that "The government did not diminish in size during Reagan's presidency, but instead grew larger than before, And it became less tethered to the law." This paradox is central to understanding the context in which the Iran-Contra affair unfolded. He left office in 1989 with the highest approval rating of any president since, a testament to his enduring popularity despite the scandals that plagued his second term.| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Ronald Wilson Reagan |

| Born | February 6, 1911, Tampico, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 5, 2004, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Political Party | Republican |

| Years in Office (President) | January 20, 1981 – January 20, 1989 |

| Key Achievements | Economic recovery ("Reaganomics"), end of the Cold War, increased national optimism, appointment of Sandra Day O'Connor to Supreme Court. |

| Major Controversies | Iran-Contra Affair, SDI ("Star Wars") program, increased national debt, response to AIDS epidemic. |

The Core of the Controversy: Presidential Knowledge

The central and most contentious question surrounding the Iran-Contra affair is undoubtedly: did Reagan know about Iran-Contra? The answer remains elusive and complex, mired in conflicting testimonies, strategic denials, and a political climate that favored plausible deniability. Officially, the Tower Commission, established by Reagan himself, concluded that while he was not directly aware of the diversion of funds to the Contras, he was ultimately responsible for the actions of his administration. However, this conclusion has been widely debated.Denials and Declarations

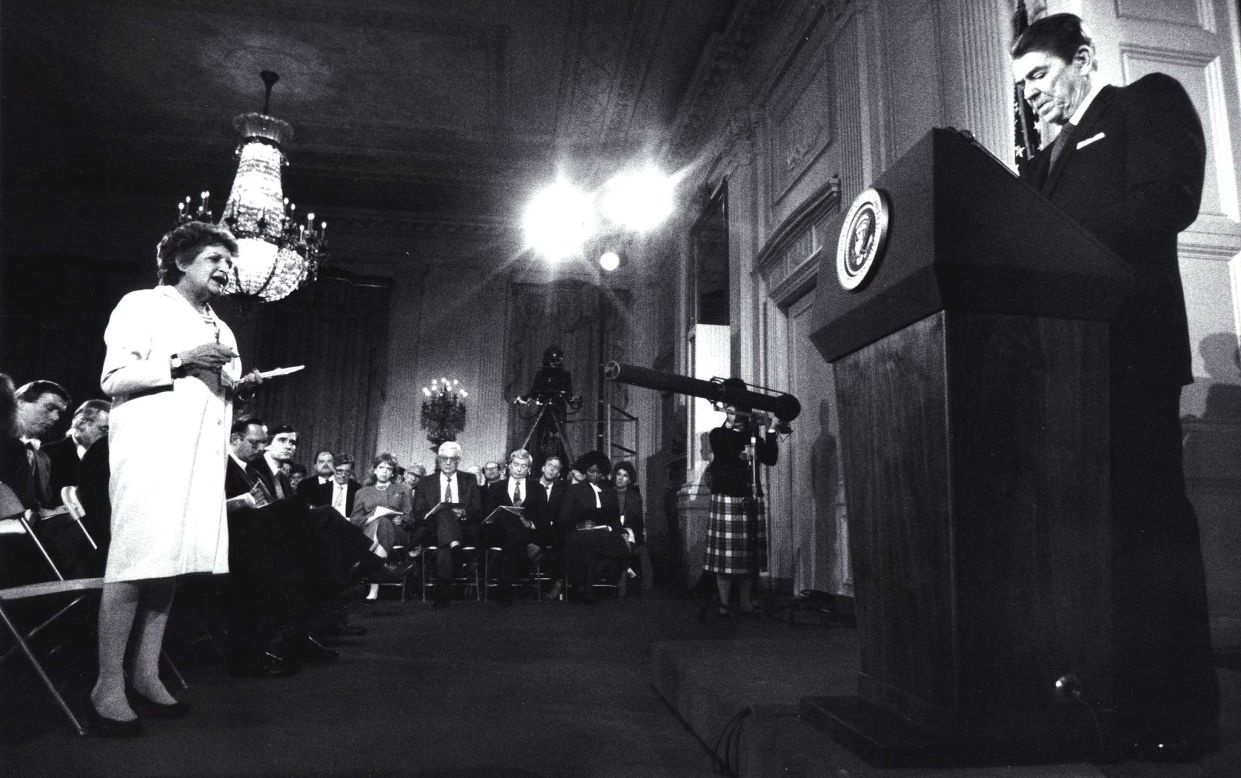

From the outset, President Reagan maintained his innocence regarding the most egregious aspects of the scandal. He consistently stated that he was unaware of the illegal diversion of funds to the Contras and the full extent of the arms-for-hostages scheme. His public stance was one of shock and disappointment upon learning the details. For instance, in his own words, he stated, "I was aware the resistance was receiving funds directly from third countries and from private efforts, and I endorsed those endeavors wholeheartedly. Indeed, I didn't know there were excess funds." This statement is crucial: it acknowledges his general awareness and endorsement of *some* external funding for the Contras but explicitly denies knowledge of the *excess funds* that were diverted from the arms sales. However, critics and investigators found this distinction increasingly difficult to accept. The sheer scale and secrecy of the operation, involving high-level officials, made it hard to believe that the President, known for his hands-on approach to foreign policy, could be completely in the dark. While the government's official position was that "there is no evidence Reagan knew his claim was false," this doesn't equate to evidence that he was truly unaware. It merely means direct, irrefutable proof of his explicit order or knowledge was not found or disclosed.The Role of Key Players and Their Accounts

The narrative surrounding Reagan's knowledge is heavily influenced by the testimonies and actions of key figures involved in the scandal. Individuals like Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, National Security Advisor John Poindexter, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, and Secretary of State George Shultz played pivotal roles. North and Poindexter, in particular, were central to the operation and claimed to have acted to protect the President, even asserting that Poindexter had deliberately withheld information from Reagan to provide him with "plausible deniability." Edwin Meese III, Reagan's Attorney General, was among the first to investigate the affair, and his initial report largely exonerated the President. However, Malcolm Byrne, a prominent historian and expert on the Iran-Contra affair, takes direct aim at Meese’s version of the story. Byrne, along with Peter Kornbluh, co-edited "The Iran-Contra Affair: The Declassified History," a seminal work on the subject. Byrne argues that "in fact," Meese's account downplayed the extent of the administration's, and potentially Reagan's, involvement. He suggests that Meese's investigation was more about damage control than a thorough pursuit of the truth. The challenge for investigators was compounded by the refusal of key individuals to fully cooperate or disclose all information. "There is evidence that Reagan did know, but key individuals refused to talk." This silence, or selective memory, from those closest to the operation, created a significant hurdle in definitively answering the question of presidential knowledge. The lack of direct testimony or smoking gun documents linking Reagan directly to the illegal diversion left a persistent ambiguity, despite widespread suspicion. For many, "there didn't seem to be any indication that that was the case here" when it came to a truly hands-off president, given the nature of the operations and the administration's deep commitment to its objectives. The very structure of "Reagan's scandal and the unchecked abuse of presidential power," as Byrne describes it, points to a systemic issue that extended beyond a few rogue operatives.Congressional Investigations and Their Findings

The Iran-Contra affair triggered a series of intense and prolonged investigations, reflecting the gravity of the constitutional crisis it presented. "There were multiple congressional investigations and a number of people went to jail." The most prominent of these were the Tower Commission, appointed by President Reagan himself, and joint hearings by the House and Senate select committees. The Tower Commission, while critical of the administration's management style and lack of oversight, largely concluded that Reagan was not directly aware of the illegal diversion of funds. However, it strongly criticized his "management style" and "hands-off" approach, suggesting it created an environment where such activities could flourish. The subsequent congressional investigations delved deeper, uncovering a vast network of covert operations, secret bank accounts, and a deliberate effort to bypass congressional authority. They revealed a pattern where the executive branch had "become less tethered to the law," a worrying trend that allowed the Iran-Contra scheme to take root. Despite extensive testimonies and the production of thousands of documents, these investigations ultimately failed to produce a definitive "smoking gun" that directly implicated President Reagan in ordering or knowing about the illegal diversion of funds. This was partly due to the deliberate efforts of some officials to destroy evidence or provide evasive testimony, as well as the inherent difficulty in proving a negative (i.e., proving someone *didn't* know). Nevertheless, the investigations led to the indictment and conviction of several high-ranking officials, including Oliver North, John Poindexter, and Caspar Weinberger, for charges ranging from perjury to obstruction of justice, though some convictions were later overturned on appeal. The fact that "a number of people went to jail" underscores the seriousness of the crimes committed, regardless of the ultimate finding on presidential knowledge.The Legacy of Iran-Contra and Presidential Power

The Iran-Contra affair left an indelible mark on American politics and the perception of presidential power. It highlighted the dangers of an executive branch operating with excessive secrecy and a disregard for congressional oversight. The scandal led to intense debates about the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches, and the extent to which a president can conduct foreign policy without accountability. The phrase "the politics of presidential recovery" became relevant as the administration sought to regain public trust and control the narrative. While Reagan's personal popularity remained remarkably high—he "left office with the highest approval rating of any president since"—the scandal fundamentally altered the public's understanding of presidential accountability. It underscored how easily the "government... became less tethered to the law" under the guise of national security. Some critics, fueled by the revelations, went as far as to suggest impeachment. However, as one observer noted, "I hate Reagan and the populism he unleashed in the US, but I disagree that they could have impeached him at all." This sentiment reflects the political realities of the time, where despite the gravity of the scandal, Reagan's public support and the broader political currents, particularly the rise of neoliberalism, made such an extreme measure unlikely. "There was nothing that would really stop neoliberalism in that era," suggesting a broader political momentum that overshadowed even significant controversies. The affair served as a stark warning about the potential for unchecked executive power and the need for robust checks and balances in a democratic system.The Nicaragua Connection: Context and Strategy

The Iran-Contra affair cannot be fully understood without examining its roots in the Reagan administration's fervent anti-communist foreign policy, particularly concerning Nicaragua. The Sandinista government, which came to power in 1979, was viewed by Reagan as a Soviet proxy threatening U.S. interests in Central America. Consequently, supporting the Contra rebels became a cornerstone of his foreign policy agenda. "A large part of the Reagan administration’s strategy was to discredit the new Sandinista government." This was not merely about military aid but a comprehensive effort to destabilize and undermine the regime through various means, including covert operations. When Congress, through the Boland Amendment, explicitly prohibited direct or indirect U.S. government aid to the Contras, the administration felt compelled to find alternative funding sources. This congressional restriction was the direct catalyst for the illegal diversion of funds from the Iranian arms sales. The administration's determination stemmed from a belief that Central America, despite its perceived strategic unimportance to some, was crucial in the broader Cold War context. As one assessment noted, "Reagan could afford to support the calamitous regimes in the region not because of the region’s importance but because of its unimportance, The fallout that resulted from a hard line there, it was thought, could be managed or easily ignored." This perspective suggests a calculated risk: that even if the operations were discovered, the political fallout from supporting anti-communist forces in a seemingly peripheral region would be manageable or easily dismissed by the public. This miscalculation proved costly, as the scandal exploded into a major constitutional crisis, proving that even seemingly "unimportant" regions could trigger significant domestic political repercussions.The Bush Factor: A Successor's Shadow

The question of knowledge about Iran-Contra extends beyond Ronald Reagan to his Vice President and successor, George H.W. Bush. "Reagan was succeeded as president by his vice president, George H.W." Bush, having served eight years as Reagan's second-in-command, was inevitably drawn into the periphery of the scandal. His role and knowledge became a significant point of contention during his own presidential campaign and subsequent administration. While Bush consistently denied direct knowledge of the illegal diversion of funds, his proximity to the President and his role in national security meetings raised suspicions. "There is evidence of Bush's involvement with Iran-Contra as well," though like Reagan, direct, irrefutable proof of his explicit knowledge of the illegalities remained elusive. Independent counsel Lawrence Walsh's investigation into Iran-Contra extended into Bush's presidency, leading to the indictment of former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger just before the 1992 election, a move that sparked considerable controversy. The lingering questions about Bush's involvement underscored the pervasive nature of the scandal, suggesting that the culture of secrecy and covert operations extended through the highest echelons of the administration, raising the question of just how much did Reagan know about Iran-Contra and how much was shared with his closest advisors.Conclusion: An Enduring Question The Iran-Contra affair remains one of the most perplexing and significant political scandals in modern American history. The central question—did Reagan know about Iran-Contra?—continues to defy a simple, definitive answer. While no direct, irrefutable evidence emerged to prove that President Reagan explicitly ordered or was fully aware of the illegal diversion of funds, the circumstantial evidence, the testimonies of key players, and the culture of secrecy within his administration strongly suggest a president who, at the very least, fostered an environment where such actions were not only possible but encouraged. His admitted awareness of external funding for the Contras, coupled with the widespread disregard for congressional mandates, paints a picture of a presidency that "became less tethered to the law." Despite the scandal, Ronald Reagan's popularity remained largely intact; he "left office with the highest approval rating of any president since." This phenomenon, often attributed to his charismatic leadership and the public's desire to believe in their president, highlights the complex interplay between public perception, political realities, and the pursuit of justice. The Iran-Contra affair stands as a powerful reminder of the enduring tension between executive power and democratic accountability, and the critical importance of transparency in government. The full truth of what Reagan knew may never be definitively known, leaving the scandal as a permanent, cautionary tale in the annals of American political history. What are your thoughts on Reagan's knowledge of Iran-Contra and its lasting impact on American politics? Share your perspective in the comments below. For more insights into pivotal moments in American history, explore our other articles on executive power and foreign policy.

Iran-contra affair hearings in Congress preceded Jan. 6 panel - The

Notable leakers and whistle-blowers | CNN

Ronald Reagan - Iran-Contra, Cold War, President | Britannica